Christianity and violence

Christianity and violence

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Christianity and violence have been associated repeatedly during history, both in acts of violence and in opposition to such violence.[1]

Such religious violence has been carried out by persons, organizations, or institutions in furtherance of Christian dogma, or in support of those who share their beliefs.[2] In Letter to a Christian Nation, critic of religion Sam Harris writes that "...faith inspires violence in at least two ways. First, people often kill other human beings because they believe that the creator of the universe wants them to do it... Second, far greater numbers of people fall into conflict with one another because they define their moral community on the basis of their religious affiliation..."[3]

There is also a strong doctrinal and historical imperative within Christianity against violence,[4] and Christianity includes prominent traditions of nonviolence. During the first few centuries of the religion's existence, Christians were strict pacifists.[5]

Contents[hide] |

[edit] Christian opposition to violence

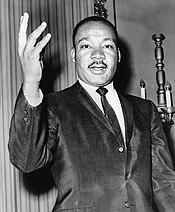

Despite the occurrence of violence by some Christians, Christianity has a long tradition of opposition to violence. Some early figures in Christian thought explicitly disavowed violence. Origen wrote: "Christians could never slay their enemies. For the more that kings, rulers, and peoples have persecuted them everywhere, the more Christians have increased in number and grown in strength."[6]Clement of Alexandria wrote: "Above all, Christians are not allowed to correct with violence."[7] Several present-day Christian churches and communities were established specifically with nonviolence, including conscientious objection to military service, as foundations of their beliefs.[8] In the twentieth century, Martin Luther King, Jr. adapted the nonviolent ideas of Gandhi to a Baptist theology and politics.[9] In the twenty-first century, Christian feminist thinkers have drawn attention to opposing violence against women.[10]

In response to the accusations of Richard Dawkins, Alister McGrath suggests that, far from endorsing "out-group hostility", Jesus commanded an ethic of "out-group affirmation". McGrath agrees that it is necessary to critique religion, but says that that it possesses internal means of reform and renewal, and argues that, while Christians may certainly be accused of failing to live up to Jesus' standard of acceptance, Christian ethics reject violence.[11]

[edit] Christian thought on justified violence

Religious scholar Mark Juergensmeyer wrote: "It is good to remember, however, that despite its central tenets of love and peace, Christianity—like most traditions—has always had a violent side. The bloody history of the tradition has provided images as disturbing as those provided by Islam or Sikhism, and violent conflict is vividly portrayed in the Bible. This history and these biblical images have provided the raw material for theologically justifying the violence of contemporary Christian groups. Attacks on abortion clinics, for instance, have been viewed not only as assaults on a practice that Christians regard as immoral, but also as skirmishes in a grand confrontation between forces of evil and good that has social and political implications."[12]:19-20 The statement attributed to Jesus "I come not to bring peace, but to bring a sword" has been interpreted by some as a call to arms to Christians.[12]

[edit] Holy war

Theologian Robert McAfee Brown identifies a succession of three basic attitudes towards violence and war during the history of Christian thought.[5] The earliest Christians were strict pacifists, while by around the third century CE, the concept of just war emerged, later to be expanded to include holy war or crusade.

According to Jared Diamond, Saint Augustine played a critical role in delineating Christian thinking about what constitutes a just war, and about how to reconcile Christian teachings of peace with the need for war in certain situations.[13] Augustine concluded that war could be justified to protect the innocent or for self-defense, but that wars of aggression are unjust and that it is never acceptable to target neutral parties.

During the medieval period, Pope Gregory VII and Pope Urban II sanctified the concept of holy war by allowing knights to obtain remission of sins "in and through the exercise of his martial skills" as opposed to giving alms, and defined holy war as "a war that confers positive spiritual merit on those who fight in it."[14][15]

Daniel Chirot argued that the Biblical account of Joshua and the Battle of Jericho was used to justify the genocide of Catholics during the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland.[16]:3 Chirot also interprets 1 Samuel 15:1-3 as "the sentiment, so clearly expressed, that because a historical wrong was committed, justice demands genocidal retribution."[16]:7-8

In the twentieth century, the concept of just war was further extended by critics of capitalism in Latin America, to justify the overthrow of governments deemed to be oppressive to the poor, as one branch of the liberation theology movement.[17]

[edit] See also

[edit] Violence against Christians |

[edit] References

- ^ Nuttall, Geoffrey Fillingham (1972). Christianity and violence. Priory Press. http://books.google.com/books?id=enfYGwAACAAJ&dq=%22Christianity+and+violence%22+-inpublisher:icon&as_brr=0&cd=1. Retrieved May 19, 2010.

- ^ B. Hoffman, "Inside Terrorism", Columbia University Press, 1999, p. 105–120.

- ^ Sam Harris (2006). Letter to a Christian Nation. Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 80–81. ISBN 9780307265777.

- ^ J. Denny Weaver (2001). "Violence in Christian Theology". Cross Currents. http://www.crosscurrents.org/weaver0701.htm#TEXT1. Retrieved 2009-08-17.

- ^ a b Brown, Robert McAfee (1987). Religion and Violence (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: The Westminster Press. p. 18. ISBN 066424078X. http://books.google.com/books?id=BYY0gYPhzQQC&pg=PA3&dq=%22Christianity+and+violence%22+-inpublisher:icon&lr=&as_brr=0&cd=12#v=onepage&q=%22Christianity%20and%20violence%22%20-inpublisher%3Aicon&f=false.

- ^ Origen: Contra Celsus, Book 7 (Roberts-Donaldson)

- ^ Clement of Alexandria: Fragments

- ^ Speicher, Sara and Durnbaugh, Donald F. (2003), Ecumenical Dictionary: Historic Peace Churches

- ^ King, Jr., Martin Luther; Clayborne Carson; Peter Holloran; Ralph Luker; Penny A. Russell (1992). The papers of Martin Luther King, Jr.. University of California Press. ISBN 0520079507.

- ^ Hood, Helen (2003). "Speaking Out and Doing Justice: It’s No Longer a Secret but What are the Churches Doing about Overcoming Violence against Women?". EBSCO Publishing. pp. 216–225. http://familyunitednetwork.com/Documents/Religious/gender%20churches%20and%20violence.pdf. Retrieved May 19, 2010.

- ^ Alister McGrath and Joanna Collicutt McGrath, The Dawkins Delusion?, Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 2007, ISBN 978-0-281-05927-0

- ^ a b Mark Juergensmeyer (2004). Terror in the Mind of God: The Global Rise of Religious Violence. University of California Press. ISBN 0520240111.

- ^ Diamond, Jared (2008). 1000 Events That Shaped the World. National Geographic Society. p. 74. ISBN 1426203144. http://books.google.com/books?id=8AceAd-41awC&pg=PA74&dq=%22Christianity+and+violence%22+-inpublisher:icon&lr=&as_brr=0&cd=28#v=onepage&q=%22Christianity%20and%20violence%22%20-inpublisher%3Aicon&f=false.

- ^ E. Randolph Daniel (1978). "The Holy War (review)". Speculum 53 (3): 602–603.

- ^ Thomas Patrick Murphy, editor (1976). The holy war. Conference on Medieval and Renaissance Studies, Ohio State University Press.

- ^ a b Daniel Chirot. Why Some Wars Become Genocidal and Others Don't. Jackson School of International Studies, University of Washington. http://jsis.artsci.washington.edu/jsis/Chirot-War.pdf.

- ^ Sigmund, Paul E. (Winter 1991). "Christianity and violence: The case of liberation theology". Terrorism and Political Violence (Routledge, Taylor & Francis) 3 (4): 63–79. doi:10.1080/09546559108427127. http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/content~content=a788812522&db=all.

[edit] Bibliography

- Hedges, Chris. 2007. American Fascists: The Christian Right and the War on America. Free Press.

- Lea, Henry Charles. 1961. The Inquisition of the Middle Ages. Abridged. New York: Macmillan.

- Mason, Carol. 2002. Killing for Life: The Apocalyptic Narrative of Pro-Life Politics. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Tyerman, Christopher. 2006. God's War: A New History of the Crusades. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, Belknap.

- Zeskind, Leonard. 1987. The ‘Christian Identity’ Movement, [booklet]. Atlanta, Georgia: Center for Democratic Renewal/Division of Church and Society, National Council of Churches.