Civil rights movement

Civil rights movement

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| It has been suggested that this article or section be merged into Civil and political rights. (Discuss) |

The civil rights movement was a worldwide political movement for equality before the law occurring between approximately 1950 and 1980. It was accompanied by much civil unrest and popular rebellion. The process was long and tenuous in many countries, and most of these movements did not achieve or fully achieve their objectives. In its later years, the civil rights movement took a sharp turn to the radical left in many cases.

Civil rights movement in Northern Ireland

| This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone or spelling. You can assist by editing it. (December 2008) |

| This article may be inaccurate in or unbalanced towards certain viewpoints. Please improve the article by adding information on neglected viewpoints, or discuss the issue on the talk page. (January 2010) |

Northern Ireland is a province of United Kingdom which has witnessed violence over many decades mainly because of sectarian tensions between the Catholic and Protestant community, known as the Troubles.

The civil rights struggle in Northern Ireland can be traced to Catholics in Dungannon who were fighting for better housing for the members of the Catholic community. This domestic issue would not have led to a fight for civil rights if the policies of Northern Ireland did not make being a registered householder the qualification for the local government franchise. Thus these Catholics were not only challenging what they saw as unfair housing policies, they were also taking the first steps toward fighting for civil rights for their community. Using various means to defend and improve the conditions for their communities, these Catholics were in fact preparing a large part of the Christian population to move beyond local and domestic issue and to embrace the larger purpose of the civil rights battle. This substantial contribution made by women is often erased from the general history of Northern Ireland primarily because this country still has a Protestant majority and a conservative culture who often overlook the role of women in the political sphere. [1].

On a broader and more organized front, in January 1952, the Campaign for Social Justice (CSJ) was launched officially in Belfast. This organization took over the woman's struggle over better housing and committed itself to end the discrimination in employment. The CSJ promised the Catholic community that their cries would be heard. They challenged the government, promising that they would take their case to the Commission for Human Rights in Strasbourg and to the United Nations[2].

Having started with basic domestic issues, the civil rights struggle in Northern Ireland escalated to a full scale movement that found its embodiment in the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association. NICRA campaigned in the late sixties and early seventies and consciously modeled itself on the civil rights movement in the United States. Empowered by what African Americans were doing, the movement took on marches and protest to demand better conditions for the minority of Catholics who lived in the Protestant state. Republican leader Gerry Adams explained that Catholics saw that it was possible for them to have their demands heard. He wrote that "we were able to see an example of the fact that you didn't just have to take it, you could fight back"[2].

NICRA originally had five main demands:

- one man, one vote

- an end to discrimination in housing

- an end to discrimination in local government

- an end to the gerrymandering of district boundaries, which limited the effect of Catholic voting

- the disbandment of the B-Specials, an entirely Protestant Police reserve, perceived as sectarian.

All of these specific demands were aimed at an ultimate goal that had been the one of women at the very beginning: the end to discriminations.

Civil rights activists all around Northern Ireland soon launched a campaign of civil disobedience. There was opposition from Loyalists, who were aided by the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), Northern Ireland's Police Force.{fact} At this point, the RUC was over 90% Protestant in its make-up. Violence escalated, resulting in the rise of the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) from the Catholic community, a reminiscent group from the War of Independence and the Civil War that occurred in the 1920s – this group launched a campaign of violence to end British government presence in Northern Ireland. Loyalist paramilitaries responded with a defensive campaign of violence. The British government responded with a policy of internment without trial of suspected IRA members. For more than three hundred people, the internment lasted several years. The huge majority of those interned by the British forces were Catholic. In 1978, in a case brought by the government of the Republic of Ireland against the government of the United Kingdom, the European Court of Human Rights ruled that the interrogation techniques approved for use by the British army on internees in 1971 amounted to "inhuman and degrading" treatment.

Although it is common knowledge that, for a time, the aims of the Republicans was for their military division, the IRA, and those of NICRA to converge, the two bodies never did. The IRA told the Republicans to join in the civil rights movement but it never controlled NICRA. The Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association fought for the end of discrimination toward Catholics and it was happy to do so within the British state [3].

One of the most important events in the era of civil rights in Northern Ireland took place in Derry, it was an event that changed the peaceful movement who used civil disobedience into an armed conflict. The Battle of the Bogside started on 12 August when an Apprentice Boys parade – a Protestant order – passed through Waterloo Place, where a large crowd was gathered at the mouth of William Street, on the edge of the Bogside. Different accounts described the first outbreak of violence either as an attack by youths from the Bogside on the R.U.C or as an outbreak of fighting between Protestants and Catholics. Either way, the violence escalated in the neighborhood called the Bogside, where barricades were erected. Proclaiming this district to be the Free Derry, Bogsiders carry on fights with the RUC for days using stones and petrol bombs. The government finally withdrew the RUC and instead sent the army to disband the crowds of Catholics who were barricaded in the Bogside [4].

Bloody Sunday in Derry is seen as a turning point in the civil rights movement. On this day, the Catholics were trying a peaceful way of resolving the problem. But they were ignored and fights broke out. Fourteen Catholic Civil rights marchers protesting against internment were shot dead by the British army and many were left wounded on the streets.

The peace process has made significant gains in recent years. Through open dialogue from all parties, a lasting ceasefire from all paramilitary groups has lasted. A strong economy and more opportunities for all citizens has greatly improved Northern Ireland's standard of living. Civil rights issues have become far less of a concern for many in Northern Ireland over the past twenty years as laws and policies protecting their rights and forms of affirmative action have been implemented for all government offices and many private businesses. Tensions still exist in some corners of the province, but the vast majority of citizens are no longer affected by the violence that once paralyzed the province.

Movements of Independence in Africa

A wave of independence movements in Africa crested in the 1960s. This included the Angolan War of Independence, the Guinea-Bissauan Revolution, the war of liberation in Mozambique and the struggle against apartheid in South Africa. This wave of struggles re-energised pan-Africanism, and led to the founding of the Organization of African Unity (OAU) in 1963.

Canada's Quiet Revolution

The 1960's brought intense political and social change to the Canadian province of Quebec with the election of Liberal Premiere Jean Lesage after the death of Maurice Duplessis, who's government was widely viewed as corrupt[5]. Changes included secularization of the education system and health care which were both heavily controlled by the Roman Catholic Church, who's support for Duplessis and perceived corruption had angered most Quebecois. Policies of the Liberals government also sought to give Quebec more economic autonomy, such as the nationalization of Hydro-Quebec and the creation of public companies for the mining, forestry, iron/steel and petroleum industries of the province. Other changes included the creation of the Régie des Rentes du Québec (Quebec Pension Plan) and new labour codes that made unionizing easier and gave workers the right to strike.

The social and economic changes of the Quiet Revolution gave life to the Quebec sovereignty movement, as more and more Quebecois saw themselves as a distinctly culturally different from the rest of Canada. The sovereignist Parti Quebecois was created in 1968, and won the 1976 Quebec general election. They enacted legislation meant to enshrine French as the language of business in the province, while also controversially restricting the usage of English on signs and restricting the eligibility of students to be taught in English.

A radical strand of French Canadian nationalism produced the Front de Libération du Québec (FLQ), which since 1963 had been using terrorism in an attempt to make Quebec a sovereign nation. In October 1970, in response to the arrest of some of its members earlier in the year, the FLQ kidnapped British diplomat James Cross and Quebec's Minister of Labour Pierre Laporte, later killing Laporte. The then Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau, himself a French Canadian, invoked the War Measures Act, declaring martial law in Quebec, and by the end of the year the kidnappers had all been arrested.

Civil rights movement in the United States

In a relatively stable political system, after a status had been reached in which every citizen has the same rights by law, practical issues of discrimination remain. Even if every person is treated equally by the state, there may not be equality due to discrimination within society, such as in the workplace, which may hinder civil liberties in everyday life. During the second half of the 20th century, Western societies introduced legislation that tried to remove discrimination on the basis of race, gender or disability.

The civil rights movement in the United States refers in part to a set of noted events and reform movements in that country aimed at abolishing public and private acts of racial discrimination and racism against African Americans and other disadvantaged groups between 1954 to 1968, particularly in the southern United States. It is sometimes referred to as the Second Reconstruction era.

Later, groups like the Black Panther Party, the Young Lords, the Weathermen and the Brown Berets turned to more harsh tactics to make a revolution that would establish, in particular, self-determination for U.S. minorities—bids that ultimately failed due in part to a coordinated effort by the United States Government's COINTELPRO efforts to subvert such groups and their activities.

Ethnicity equity issues

Integrationism

In the last decade of the nineteenth century in the United States, racially discriminatory laws and racial violence aimed at African Americans and other disadvantaged groups began to mushroom. This period is sometimes referred to as the nadir of American race relations. Elected, appointed, or hired government authorities began to require or permit discrimination, specifically in the states of Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Florida, South Carolina, North Carolina, Virginia, Arkansas, Tennessee, Oklahoma, and Kansas. There were four required or permitted acts of discrimination against African Americans. They included racial segregation – upheld by the United States Supreme Court decision in Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896 – which was legally mandated by southern states and nationwide[citation needed] at the local level of government, voter suppression or disfranchisement in the southern states, denial of economic opportunity or resources nationwide, and private acts of violence and mass racial violence aimed at African Americans unhindered or encouraged by government authorities. Although racial discrimination was present nationwide, the combination of law, public and private acts of discrimination, marginal economic opportunity, and violence directed toward African Americans in the southern states became known as Jim Crow.

Noted strategies employed prior to the civil rights movement of 1955 to 1968 to abolish discrimination against African Americans initially included litigation and lobbying attempts by organizations such as the NAACP. These efforts were a hallmark of the American Civil Rights Movement from 1896 to 1954. However, by 1955, private citizens became frustrated by gradual approaches to implement desegregation by federal and state governments and the "massive resistance" by proponents of racial segregation and voter suppression. In defiance, these citizens adopted a combined strategy of direct action with nonviolent resistance known as civil disobedience. The acts of civil disobedience produced crisis situations between practitioners and government authorities. The authorities of federal, state, and local governments often had to act with an immediate response to end the crisis situations – sometimes in the practitioners' favor. Some of the different forms of protests and/or civil disobedience employed include boycotts as successfully practiced by the Montgomery Bus Boycott (1955–1956) in Alabama – which gave the movement one of its more famous icons in Rosa Parks-, "sit-ins" as demonstrated by the influential Greensboro sit-in (1960) in North Carolina, and marches as exhibited by the Selma to Montgomery marches (1965) in Alabama. The evidence of changing attitudes could also be seen around the country, where small businesses sprang up supporting the civil rights movement, such as New Jersey's notable Everybody's Luncheonette.[6]

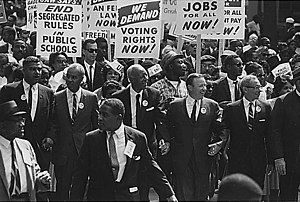

The most illustrious march is still probably the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. It is best remembered for the glorious speech Martin Luther King, Jr. gave, in which the "I have a dream" part turned into a national text and eclipsed the troubles the organizers had to bring to march forward. It had been a fairly complicated affair to bring together various leaders of civil rights, religious and labor groups. As the name of the march tells us, many compromises had to be made in order to unite the followers of so many different causes. The "March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom" emphasized the combined purposes of the march and the goals that each of the leaders aimed at. These leaders – informally named the Big Six – were A. Philip Randolph, Roy Wilkins, Martin Luther King, Whitney Young, James Farmer and John Lewis. Although they came from different political horizons, these leaders were intent on the peaceful success of the march. The march even had its own marshal, ensuring that the event would be peaceful and respectful of the law[7]. The success of the march is still being debated but one aspect has been raised in the last few years: the misrepresentation of women. A lot of feminine civil rights groups had participated in the organization of the march but when it came to actual activity, women were denied the right to speak and were relegated to figurative roles in the back of the stage. As some female participants have noticed, the March can be remembered for the "I Have a Dream" speech but for most female activists it was a new awakening, forcing black women not only to fight for civil rights but also to engage in the Feminist movement[8].

Noted achievements of the civil rights movement in this area include the judicial victory in the Brown v. Board of Education case that nullified the legal article of "separate but equal" and made segregation legally impermissible, passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964[9] that banned discrimination in employment practices and public accommodations, passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 that restored voting rights, and passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1968 that banned discrimination in the sale or rental of housing.

Black Power

By 1965 the emergence of the Black Power movement (1966–1975) began gradually to eclipse the original "integrated power" aims of the civil rights movement that had been espoused by Martin Luther King, Jr. Advocates of Black Power argued for black self-determination, and to assert that the assimilation inherent in integration robs Africans of their common heritage and dignity; e.g., the theorist and activist Omali Yeshitela argues that Africans have historically fought to protect their lands, cultures and freedoms from European colonialists, and that any integration into the society which has stolen another people and their wealth is actually an act of treason.

Today, most Black Power advocates have not changed their self-sufficiency argument. Racism still exists worldwide and it is generally accepted that blacks in the United States, on the whole, did not assimilate into U.S. "mainstream" culture either by King's integration measures or by the self-sufficiency measures of Black Power—rather, blacks arguably became evermore oppressed, this time partially by "their own" people in a new black stratum of the middle class and the ruling class. Black Power's advocates generally argue that the reason for this stalemate and further oppression of the vast majority of U.S. blacks is because Black Power's objectives have not had the opportunity to be fully carried through.

One of the most public manifestations of the Black Power movement took place in the 1968 Olympics when two African-Americans stood on the podium doing a Black Power salute. This act is still remembered today as the 1968 Olympics Black Power salute.

Chicano Movement

The Chicano Movement, also known as the Chicano Civil Rights Movement, Mexican-American Civil Rights Movement and El Movimiento, was the part of the American Civil Rights Movement that sought political empowerment and social inclusion for Mexican-Americans around a generally nationalist argument. The Chicano movement blossomed in the 1960s and was active through the late 1970s in various regions of the U.S. The movement had roots in the civil rights struggles that had preceded it, adding to it the cultural and generational politics of the era.

The early heroes of the movement—Rodolfo Gonzales in Denver, Colorado and Reies Tijerina in New Mexico—adopted a historical account of the preceding hundred and twenty-five years that had obscured much of Mexican-American history. Gonzales and Tijerina embraced a nationalism that identified the failure of the United States government to live up to its promises in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. In that account, Mexican-Americans were a conquered people who simply needed to reclaim their birthright and cultural heritage as part of a new nation, which later became known as Aztlán.

That version of the past did not, on the other hand, take into account the history of those Mexicans who had immigrated to the United States. It also gave little attention to the rights of undocumented immigrants in the United States in the 1960s—not surprisingly, since immigration did not have the political significance it was to acquire. It was a decade later when activists, such as Bert Corona in California, embraced the rights of undocumented workers and helped broaden the movement to include their issues.

When the movement dealt with practical problems in the 1960s, most activists focused on the most immediate issues confronting Mexican-Americans: unequal educational and employment opportunities, political disfranchisement, and police brutality. In the heady days of the late 1960s, when the student movement was active around the globe, the Chicano movement brought about more or less spontaneous actions, such as the mass walkouts by high school students in Denver and East Los Angeles in 1968 and the Chicano Moratorium in Los Angeles in 1970.

The movement was particularly strong at the college level, where activists formed MEChA, Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán, which promoted Chicano Studies programs and a generalized ethno-nationalist agenda.

American Indian Movement

At a time when peaceful sit-ins were a common protest tactic, the American Indian Movement (AIM) takeovers in their early days were noticeably forceful. Some appeared to be spontaneous outcomes of protest gatherings, but others included armed seizure of public facilities, such as in the Wounded Knee incident.

The Alcatraz Island occupation of 1969, although commonly associated with NAM, pre-dated the organization but was a catalyst for its formation.

In 1970 AIM occupied abandoned property at the Naval Air Station near Minneapolis, Minnesota. In July 1971, AIM assisted a takeover of the Winter Dam, Lac Courte Oreilles, and Wisconsin. When activists took over the Bureau of Indian Affairs Headquarters in Washington D.C. in November 1972, they sacked the building, and 24 people were arrested. Activists occupied the Custer County Courthouse in 1973, though police routed the occupation after a riot took place.

In 1973 activists and military forces confronted each other in the Wounded Knee incident. The standoff lasted 71 days, and two men died in the violence.

Gender equity issues

If the period associated with first-wave feminism focused upon absolute rights such as suffrage (which led to women attaining the right to vote in the early part of the 20th century), the period of the second-wave feminism was concerned with the issues such as changing social attitudes and economic, reproductive, and educational equality (including the ability to have careers in addition to motherhood, or the right to choose not to have children) between the genders and addressed the rights of female minorities. The new feminist movement, which spanned from 1963 to 1982, explored economic equality, political power at all levels, professional equality, reproductive freedoms, sexuality, issues with the family, educational equality, sexuality, and many other issues.

LGBT rights and gay liberation

Since the mid 19th century in Germany, social reformers have used the language of civil rights to argue against the oppression of same-sex sexuality, same-sex emotional intimacy, and gender variance. Largely, but not exclusively, these LGBT movements have characterized gender variant and homosexually-oriented people as a minority group or groups; this was the approach taken by the homophile movement of the 1940s, 50s and early 60s. With the rise of secularism in the West, an increasing sexual openness, women's liberation, the 1960s counterculture, and a range of new social movements, the homophile movement underwent a rapid growth and transformation, with a focus on building community and unapologetic activism. This new phase came to be known as Gay Liberation.

The words "Gay Liberation" echoed "Women's Liberation"; the Gay Liberation Front consciously took its name from the National Liberation Fronts of Vietnam and Algeria; and the slogan "Gay Power", as a defiant answer to the rights-oriented homophile movement, was inspired by Black Power and Chicano Power. The GLF's statement of purpose explained:

"We are a revolutionary group of men and women formed with the realization that complete sexual liberation for all people cannot come about unless existing social institutions are abolished. We reject society's attempt to impose sexual roles and definitions of our nature."

– GLF statement of purpose

GLF activist Martha Shelley wrote,

"We are women and men who, from the time of our earliest memories, have been in revolt against the sex-role structure and nuclear family structure."

– "Gay is Good", Martha Shelley, 1970

Gay Liberationists aimed as transforming fundamental concepts and institutions of society, such as gender and the family. In order to achieve such liberation, consciousness raising and direct action were employed. Specifically, the word 'gay' was preferred to previous designations such as homosexual or homophile; some saw 'gay' as a rejection of the false dichotomy heterosexual/homosexual. Lesbians and gays were urged to "come out" and publicly reveal their sexuality to family, friends and colleagues as a form of activism, and to counter shame with gay pride. "Gay Lib" groups were formed in the Western world, in Australia, New Zealand, Germany, France, the UK, U.S., Italy and elsewhere. The lesbian group Lavender Menace was also formed in the U.S. in response to both the male domination of other Gay Lib groups and the anti-lesbian sentiment in the Women's Movement. Lesbianism was advocated as a feminist choice for women, and the first currents of lesbian separatism began to emerge.

By the late 1970s, the radicalism of Gay Liberation was eclipsed by a return to a more formal movement that became known as the Gay and Lesbian Rights Movement.

German student movement

The civil rights movement in Germany was a left-wing backlash against the post-Nazi Party era of the country, which still contained many of the conservative policies of both that era and of the pre-World War I Kaiser monarchy. The movement took place mostly among disillusioned students and was largely a protest movement analogous to others around the globe during the late 1960s. It was largely a reaction against the perceived authoritarianism and hypocrisy of the German government and other Western governments, and the poor living conditions of students. A wave of protests – some violent – swept Germany, further fueled by over-reaction by the police and encouraged by other near-simultaneous protest movements, across the world. Following more than a century of conservatism among German students, the German student movement also marked a significant major shift to the left-wing and radicalization of student politics.

France 1968

A general strike broke out across France in May 1968. It quickly began to reach near-revolutionary proportions before being discouraged by the French Communist Party, and finally suppressed by the government, which accused the communists of plotting against the Republic. Some philosophers and historians have argued that the rebellion was the single most important revolutionary event of the 20th century because it wasn't participated in by a lone demographic, such as workers or racial minorities, but was rather a purely popular uprising, superseding ethnic, cultural, age and class boundaries.

It began as a series of student strikes that broke out at a number of universities and high schools in Paris, following confrontations with university administrators and the police. The de Gaulle administration's attempts to quash those strikes by further police action only inflamed the situation further, leading to street battles with the police in the Latin Quarter, followed by a general strike by students and strikes throughout France by ten million French workers, roughly two-thirds of the French workforce. The protests reached the point that de Gaulle created a military operations headquarters to deal with the unrest, dissolved the National Assembly and called for new parliamentary elections for 23 June 1968.

The government was close to collapse at that point (De Gaulle had even taken temporary refuge at an airforce base in Germany), but the revolutionary situation evaporated almost as quickly as it arose. Workers went back to their jobs, urged on by the Confédération Générale du Travail, the leftist union federation, and the Parti Communiste Français (PCF), the French Communist Party. When the elections were finally held in June, the Gaullist party emerged even stronger than before.

Most of the protesters espoused left-wing causes, communism or anarchism. Many saw the events as an opportunity to shake up the "old society" in many social aspects, including methods of education, sexual freedom and free love. A small minority of protesters, such as the Occident group, espoused far-right causes.

On 29 May several hundred thousand protesters led by the CGT marched through Paris, chanting "Adieu, de Gaulle!", "Goodby, de Gaulle!".

While the government appeared to be close to collapse, de Gaulle chose not to say adieu. Instead, after ensuring that he had sufficient loyal military units mobilized to back him if push came to shove, he went on the radio the following day (the national television service was on strike) to announce the dissolution of the National Assembly, with elections to follow on 23 June. He ordered workers to return to work, threatening to institute a state of emergency if they did not.

From that point the revolutionary feeling of the students and workers faded away. Workers gradually returned to work or were ousted from their plants by the police. The national student union called off street demonstrations. The government banned a number of left organizations. The police retook the Sorbonne on 16 June. De Gaulle triumphed in the elections held in June and the crisis had ended.

Tlatelolco massacre, Mexico

The Tlatelolco massacre, also known as Tlatelolco's Night (from a book title), took place on the afternoon and night of October 2, 1968, in the Plaza de las Tres Culturas in the Tlatelolco section of Mexico City. The death toll remains uncertain: some estimates place the number of deaths in the thousands, but most sources report 200–300 deaths. Many more were wounded, and several thousand arrests occurred.

The massacre was preceded by months of political unrest in the Mexican capital, echoing student demonstrations and riots all over the world during 1968. The Mexican students wanted to exploit the attention focused on Mexico City for the 1968 Summer Olympics. President Gustavo Díaz Ordaz, however, was determined to stop the demonstrations and, in September, he ordered the army to occupy the campus of the National Autonomous University of Mexico, the largest university in Latin America. Students were beaten and arrested indiscriminately. Rector Javier Barros Sierra resigned in protest on September 23.

Student demonstrators were not deterred, however. The demonstrations grew in size, until on October 2, after student strikes lasting nine weeks, 15,000 students from various universities marched through the streets of Mexico City, carrying red carnations to protest the army's occupation of the university campus. By nightfall, 5,000 students and workers, many of them with spouses and children, had congregated outside an apartment complex in the Plaza de las Tres Culturas in Tlatelolco for what was supposed to be a peaceful rally. Among their chants were México – Libertad – México – Libertad ("Mexico – Liberty – Mexico –Liberty"). Rally organizers attempted to call off the protest when they noticed an increased military presence in the area.

The massacre began at sunset when army and police forces—equipped with armored cars and tanks—surrounded the square and began firing live rounds into the crowd, hitting not only the protestors, but also other people who were present for reasons unrelated to the demonstration. Demonstrators and passersby alike, including children, were caught in the fire; soon, mounds of bodies lay on the ground. The killing continued through the night, with soldiers carrying out mopping-up operations on a house-to-house basis in the apartment buildings adjacent to the square. Witnesses to the event claim that the bodies were later removed in garbage trucks.

The official government explanation of the incident was that armed provocateurs among the demonstrators, stationed in buildings overlooking the crowd, had begun the firefight. Suddenly finding themselves sniper targets, the security forces had simply returned fire in self-defense.

Prague Spring

The Prague Spring (Czech: Pražské jaro, Slovak: Pražská jar, Russian: пражская весна) was a period of political liberalization in Czechoslovakia starting January 5, 1968 and running until August 20 of that year when the Soviet Union and its Warsaw Pact allies (except for Romania) invaded the country.

During World War II Czechoslovakia fell into the Soviet sphere of influence, the Eastern Bloc. Since 1948 there were no parties other than the Communist Party in the country and it was indirectly managed by the Soviet Union. Unlike other countries of Central and Eastern Europe, the communist take-over in Czechoslovakia in 1948 was, although as brutal as elsewhere, a genuine popular movement. Reform in the country did not lead to the convulsions seen in Hungary.

Towards the end of World War II Joseph Stalin wanted Czechoslovakia, and signed an agreement with Winston Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt, that Prague would be liberated by the Red Army despite the fact that the United States Army under General George S. Patton could have liberated the city earlier. This was important for the spread of pro-Russian (and pro-communist) propaganda that came right after the war. People still remembered what they felt as Czechoslovakia's betrayal by the West at the Munich Agreement. For these reasons the people voted for communists in the 1948 elections – the last democratic poll for a long time.

From the middle of the 1960s Czechs and Slovaks showed increasing signs of rejection of the existing regime. This change was reflected by reformist elements within the communist party by installing Alexander Dubček as party leader. Dubček's reforms of the political process inside Czechoslovakia, which he referred to as Socialism with a human face, did not represent a complete overthrow of the old regime, as was the case in Hungary in 1956. Dubček's changes had broad support from the society, including the working class. However, it was still seen by the Soviet leadership as a threat to their hegemony over other states of the Eastern Bloc and to the very safety of the Soviet Union. Czechoslovakia was in the middle of the defensive line of the Warsaw Pact and its possible defection to the enemy was unacceptable during the Cold War.

However a sizeable minority in the ruling party, especially at higher leadership levels, was opposed to any lessening of the party's grip on society and they actively plotted with the leadership of the Soviet Union to overthrow the reformers. This group watched in horror as calls for multi-party elections and other reforms began echoing throughout the country.

Between the nights of August 20 and August 21, 1968, Eastern Bloc armies from five Warsaw Pact countries invaded Czechoslovakia. During the invasion, Soviet tanks ranging in numbers from 5,000 to 7,000 occupied the streets. They were followed by a large number of Warsaw Pact troops ranging from 200,000 to 600,000.

The Soviets insisted that they had been invited to invade the country, stating that loyal Czechoslovak Communists had told them that they were in need of "fraternal assistance against the counter-revolution". A letter which was found in 1989 proved an invitation to invade did indeed exist. During the attack of the Warsaw Pact armies, 72 Czechs and Slovaks were killed (19 of those in Slovakia) and hundreds were wounded (up to September 3, 1968). Alexander Dubček called upon his people not to resist. He was arrested and taken to Moscow, along with several of his colleagues.

1967 Australian Referendum

On 27 May, 1967, Australians voted to amend their constitution, particularly removing Section 127, which had previously excluded Indigenous Australians from voting in State or Commonwealth elections.

Notes

- ^ Shannon, Catherine. "Women in Northern Ireland", in Chattel, Servant or Citizen: Woman's Status in Church, State and Society. Eds. Mary O'Dowd & Sabine Wichert. Historical Studies XIX (Belfast: Institute of Irish Studies Queen's University, 1995), 238–253.

- ^ a b Dooley, Brian. "Second Class citizens", in Black and Green: The Fight for Civil Rights in Northern Ireland and Black America. (London:Pluto Press, 1998), 28–48.

- ^ Dooley, Brian. "Second Class citizens", in Black and Green: The Fight for Civil Rights in Northern Ireland and Black America. (London:Pluto Press, 1998), 28–48

- ^ O'Dochartaigh, Niall. From Civil Rights to Armalites: Derry and the Birth of the Irish Troubles (Cork: Cork University Press, 1997), 1–18 and 111–152.

- ^ http://www.wednesday-night.com/Duplessis.asp

- ^ "Everybody’s Luncheonette Camden, New Jersey". http://www.freewebs.com/almasykusnyir/everybodys/index.htm.

- ^ Barber, Lucy. "In the Great Tradition: The March on Washington for Jobs ans Freedom, August 28, 1963," in Marching on Washington: The Forging of an American Political Tradition. (Berkeley: U of California Press, 2002), 141–178.

- ^ Height,Dorothy. "We wanted the voice of a women to be heard": Black women and the 1963 March on Washington", in Sisters in the Struggle: African American Women in the Civil Rights-Black Power Movement. Eds. Collier. Thomas, Bettye and V.P. Franklin. (New York: NYU press, 2001), 83–91.

- ^ Civil Rights Act of 1964

Further reading

- Manfred Berg and Martin H. Geyer; Two Cultures of Rights: The Quest for Inclusion and Participation in Modern America and Germany Cambridge University Press, 2002

- Jack Donnelly and Rhoda E. Howard; International Handbook of Human Rights Greenwood Press, 1987

- David P. Forsythe; Human Rights in the New Europe: Problems and Progress University of Nebraska Press, 1994

- Joe Foweraker and Todd Landman; Citizenship Rights and Social Movements: A Comparative and Statistical Analysis Oxford University Press, 1997

- Mervyn Frost; Constituting Human Rights: Global Civil Society and the Society of Democratic States Routledge, 2002

- Marc Galanter; Competing Equalities: Law and the Backward Classes in India University of California Press, 1984

- Raymond D. Gastil and Leonard R. Sussman, eds.; Freedom in the World: Political Rights and Civil Liberties, 1986-1987 Greenwood Press, 1987

- David Harris and Sarah Joseph; The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and United Kingdom Law Clarendon Press, 1995

- Steven Kasher; The Civil Rights Movement: A Photographic History (1954-1968) Abbeville Publishing Group (Abbeville Press, Inc.), 2000

- Francesca Klug, Keir Starmer, Stuart Weir; The Three Pillars of Liberty: Political Rights and Freedoms in the United Kingdom Routledge, 1996

- Fernando Santos-Granero and Frederica Barclay; Tamed Frontiers: Economy, Society, and Civil Rights in Upper Amazonia Westview Press, 2000

- Paul N. Smith; Feminism and the Third Republic: Women's Political and Civil Rights in France, 1918-1940 Clarendon Press, 1996

- Jorge M. Valadez; Deliberative Democracy: Political Legitimacy and Self-Determination in Multicultural Societies Westview Press, 2000

External links

- We Shall Overcome: Historic Places of the Civil Rights Movement, a National Park Service Discover Our Shared Heritage at Travel Itinerary

- A Columbia University Resource for Teaching African American History

- Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Global Freedom Struggle, an encyclopedia presented by the Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford University