Conservation movement

Conservation movement

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The conservation movement, also known as nature conservation, is a political and social movement that seeks to protect natural resources including plant and animal species as well as their habitat for the future.

The early conservation movement included fisheries and wildlife management, water, soil conservation and sustainable forestry. The contemporary conservation movement has broadened from the early movement's emphasis on use of sustainable yield of natural resources and preservation of wilderness areas to include preservation of biodiversity. Some say the conservation movement is part of the broader and more far-reaching environmental movement, while others argue that they differ both in ideology and practice. Chiefly in the United States, conservation is seen as differing from environmentalism in that it aims to preserve natural resources expressly for their continued sustainable use by humans.[1] In other parts of the world conservation is used more broadly to include the setting aside of natural areas and the active protection of wildlife for their inherent value, as much as for any value they may have for humans.

Contents[hide] |

[edit] History

The nascent conservation movement slowly developed in the 19th century, starting first in the scientific forestry methods pioneered by the Germans and the French in the 17th and 18th centuries. While continental Europe created the scientific methods later used in conservationist efforts, British India and the United States are credited with starting the conservation movement.

Foresters in India, often German, managed forests using early climate change theories (in America, see also, George Perkins Marsh) that Alexander von Humboldt developed in the mid 19th century, applied fire protection, and tried to keep the "house-hold" of nature. This was an early ecological idea, in order to preserve the growth of delicate teak trees. The same German foresters who headed the Forest Service of India, such as Dietrich Brandis and Berthold Ribbentrop, traveled back to Europe and taught at forestry schools in England (Cooper's Hill, later moved to Oxford). These men brought with them the legislative and scientific knowledge of conservationism in British India back to Europe, where they distributed it to men such as Gifford Pinchot, which in turn helped bring European and British Indian methods to the United States.

[edit] United States

[edit] Progressive Era

Both Conservationism and Environmentalism appeared in political debates during the Progressive Era in the early 20th century.

In the early 20th century there were three main positions. The laissez-faire position held that owners of private property—including lumber and mining companies, should be allowed to do anything they wished for their property.

The Conservationists, led by President Theodore Roosevelt and his close ally Gifford Pinchot, said that the laissez-faire approach was too wasteful and inefficient. In any case, they noted, most of the natural resources in the western states were already owned by the federal government. The best course of action, they argued, was a long-term plan devised by national experts to maximize the long-term economic benefits of natural resources.

Environmentalism was the third position, led by John Muir (1838–1914). Muir's passion for nature made him the most influential American environmentalist. Muir preached that nature was sacred and humans are intruders who should look but not develop. He founded the Sierra Club and remains an icon of liberalism. He was primarily responsible for defining the environmentalist position, in the debate between Conservation and environmentalism.

Environmentalism preached that nature was almost sacred, and that man was an intruder. It allowed for limited tourism (such as hiking), but opposed automobiles in national parks. It strenuously opposed timber cutting on most public lands, and vehemently denounced the dams that Roosevelt supported for water supplies, electricity and flood control. Especially controversial was the Hetch Hetchy dam in Yosemite National park, which Roosevelt approved, and which supplies the water supply of San Francisco. To this day the Sierra Club and its allies want to dynamite Hetch Hetchy and restore it to nature.

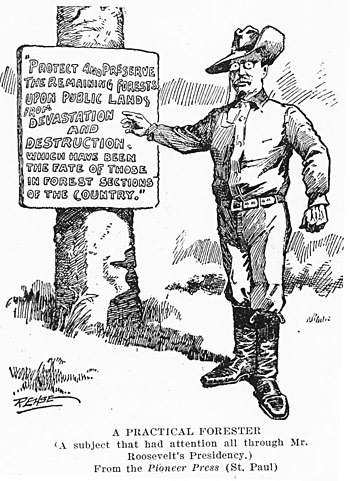

[edit] Theodore Roosevelt

Roosevelt put conservationist issue high on the national agenda.[2] He worked with all the major figures of the movement, especially his chief advisor on the matter, Gifford Pinchot. Roosevelt was deeply committed to conserving natural resources, and is considered to be the nation's first conservation President. He encouraged the Newlands Reclamation Act of 1902 to promote federal construction of dams to irrigate small farms and placed 230 million acres (360,000 mi² or 930,000 km²) under federal protection. Roosevelt set aside more Federal land for national parks and nature preserves than all of his predecessors combined.[3]

Roosevelt established the United States Forest Service, signed into law the creation of five National Parks, and signed the 1906 Antiquities Act, under which he proclaimed 18 new U.S. National Monuments. He also established the first 51 Bird Reserves, four Game Preserves, and 150 National Forests, including Shoshone National Forest, the nation's first. The area of the United States that he placed under public protection totals approximately 230,000,000 acres.

Gifford Pinchot had been appointed by McKinley as chief of Division of Forestry in the Department of Agriculture. In 1905, his department gained control of the national forest reserves. Pinchot promoted private use (for a fee) under federal supervision. In 1907, Roosevelt designated 16 million acres (65,000 km²) of new national forests just minutes before a deadline.

In May 1908, Roosevelt sponsored the Conference of Governors held in the White House, with a focus on natural resources and their most efficient use. Roosevelt delivered the opening address: "Conservation as a National Duty.".

In 1903 Roosevelt toured the Yosemite Valley with John Muir, who had a very different view of conservation, and tried to minimize commercial use of water resources and forests. Working through the Sierra Club he founded, Muir succeeded in 1905 in having Congress transfer the Mariposa Grove and Yosemite Valley to the National Park Service. While Muir wanted nature preserved for the sake of pure beauty, Roosevelt subscribed to Pinchot's formulation, "to make the forest produce the largest amount of whatever crop or service will be most useful, and keep on producing it for generation after generation of men and trees." [4]

[edit] 1930s

In the 1930s, the dominant view was the conservationism of Theodore Roosevelt, endorsed by Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt, that led to the building of many large-scale dams and water projects, as well as the expansion of the National Forest System to buy out sub-marginal farms.

[edit] Since 1970

Environmental issues reemerged on the national agenda in 1970, with Republican Richard Nixon playing a major role, especially with his creation of the Environmental Protection Agency. The debates over the public lands and environmental politics played a supporting role in the decline of liberalism and the rise of modern conservatism. Although Americans consistently rank environmental issues as "important", polling data indicates that in the voting booth voters rank the environmental issues low relative to other political concerns.

The growth of the Republican party's political power in the inland West (apart from the Pacific coast) was facilitated by the rise of popular opposition to public lands reform. Successful Democrats in the inland West and Alaska typically take more conservative positions on environmental issues than Democrats from the Coastal states. Taking the conservationist position, conservatives drew on new organizational networks of think tanks, industry groups, and citizen-oriented organizations, and they began to deploy new strategies that affirmed the rights of individuals to their property, to hunt and recreate, and to pursue happiness unencumbered by the federal government.[5]

[edit] Areas of concern

Deforestation and overpopulation are issues affecting all regions of the world. The consequent destruction of wildlife habitat has prompted the creation of conservation groups in other countries, some founded by local hunters who have witnessed declining wildlife populations first hand. Also, it was highly important for the conservation movement to solve problems of living conditions in the cities and the overpopulation of such places.

[edit] Boreal forest and the Arctic

The idea of incentive conservation is a modern one but its practice has clearly defended some of the sub Arctic wildernesses and the wildlife in those regions for thousands of years, especially by indigenous peoples such as the Evenk, Yakut, Sami, Inuit and Cree. The fur trade and hunting by these peoples have preserved these regions for thousands of years. Ironically, the pressure now upon them comes from non-renewable resources such as oil, sometimes to make synthetic clothing which is advocated as a humane substitute for fur. (See Raccoon Dog for case study of the conservation of an animal through fur trade.) Similarly, in the case of the beaver, hunting and fur trade were thought to bring about the animal's demise, when in fact they were an integral part of its conservation. For many years children's books stated and still do, that the decline in the beaver population was due to the fur trade. In reality however, the decline in beaver numbers was because of habitat destruction and deforestation, as well as its continued persecution as a pest (it causes flooding). In Cree lands however, where the population valued the animal for meat and fur, it continued to thrive. The Inuit defend their relationship with the seal in response to outside critics.[6]

[edit] Latin America (Bolivia)

The Izoceño-Guaraní of Santa Cruz, Bolivia is a tribe of hunters who were influential in establishing the Capitania del Alto y Bajo Isoso (CABI). CABI promotes economic growth and survival of the Izoceno people while discouraging the rapid destruction of habitat within Bolivia's Gran Chaco. They are responsible for the creation of the 34,000 square kilometre Kaa-Iya del Gran Chaco National Park and Integrated Management Area (KINP). The KINP protects the most biodiverse portion of the Gran Chaco, an ecoregion shared with Argentina, Paraguay and Brazil. In 1996, the Wildlife Conservation Society joined forces with CABI to institute wildlife and hunting monitoring programs in 23 Izoceño communities. The partnership combines traditional beliefs and local knowledge with the political and administrative tools needed to effectively manage habitats. The programs rely solely on voluntary participation by local hunters who perform self-monitoring techniques and keep records of their hunts. The information obtained by the hunters participating in the program has provided CABI with important data required to make educated decisions about the use of the land. Hunters have been willing participants in this program because of pride in their traditional activities, encouragement by their communities and expectations of benefits to the area.

[edit] Africa (Botswana)

In order to discourage illegal South African hunting parties and ensure future local use and sustainability, indigenous hunters in Botswana began lobbying for and implementing conservation practices in the 1960s. The Fauna Preservation Society of Ngamiland (FPS) was formed in 1962 by the husband and wife team: Robert Kay and June Kay, environmentalists working in conjunction with the Batawana tribes to preserve wildlife habitat.

The FPS promotes habitat conservation and provides local education for preservation of wildlife. Conservation initiatives were met with strong opposition from the Botswana government because of the monies tied to big-game hunting. In 1963, BaTawanga Chiefs and tribal hunter/adventurers in conjunction with the FPS founded Moremi National Park and Wildlife Refuge, the first area to be set aside by tribal people rather than governmental forces. Moremi National Park is home to a variety of wildlife, including lions, giraffes, elephants, buffalo, zebra, cheetahs and antelope, and covers an area of 3,000 square kilometers. Most of the groups involved with establishing this protected land were involved with hunting and were motivated by their personal observations of declining wildlife and habitat.

[edit] See also

- Conservation biology

- Conservation ethic

- Ecology

- Ecology movement

- Environmental movement

- Environmental protection

- Environmentalism

- Forest protection

- Habitat conservation

- List of environmental organizations

- List of environment topics

- Natural environment

- Natural landscape

- The Evolution of the Conservation Movement, 1850–1920

- Water conservation

- Wildlife conservation

- Wildlife management

[edit] References

- ^ Gifford, John C. (1945). Living by the Land. Coral Gables, Florida: Glade House. pp. 8. ASIN B0006EUXGQ.

- ^ Douglas G. Brinkley, The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America (2009)

- ^ W. Todd Benson, President Theodore Roosevelt's Conservations Legacy (2003)

- ^ Gifford Pinchot, Breaking New Ground, (1947) p. 32.

- ^ Turner (2009)

- ^ "Inuit Ask Europeans to Support Its Seal Hunt and Way of Life". 6 March 2006. http://www.icc.gl/UserFiles/File/sealskin/2006-03-07_icc_saelskind_pressemeddelse_eng.pdf. Retrieved 12 July 2007.

[edit] Further reading

- Barton, Gregory A. Empire Forestry and the Origins of Environmentalism, Cambridge University Press, 2001

- Bolaane, Maitseo. "Chiefs, Hunters & Adventurers: The Foundation of the Okavango/Moremi National Park, Botswana". Journal of Historical Geography. 31.2 (Apr. 2005): 241-259.

- Clover, Charles. 2004. The End of the Line: How overfishing is changing the world and what we eat. Ebury Press, London. ISBN 0-09-189780-7

- Hay, Peter. Main Currents in Western Environmental Thought (2002), standard scholarly history excerpt and text search

- Noss, Andrew and Imke Oetting. "Hunter Self-Monitoring by the Izoceño -Guarani in the Bolivian Chaco". Biodiversity & Conservation. 14.11 (2005): 2679-2693.

[edit] United States

- Arnold, Ron. At the Eye of the Storm: James Watt and the Environmentalists (1982), from conservative perspective

- Bates, J. Leonard. "Fulfilling American Democracy: The Conservation Movement, 1907 to 1921", The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Vol. 44, No. 1. (Jun., 1957), pp. 29–57. in JSTOR

- Brinkley, Douglas G. The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America, (2009) excerpt and text search

- Cawley, R. McGreggor. Federal Land, Western Anger: The Sagebrush Rebellion and Environmental Politics (1993), on conservatives

- Dunlap, Riley E., and Michael Patrick Allen. "Partisan Differences on Environmental Issues: A Congressional Roll- Call Analysis," Western Political Quarterly, 29 (Sept. 1976), 384–97. in JSTOR

- Flippen, J. Brooks. Nixon and the Environment (2000).

- Hays, Samuel P. Beauty, Health, and Permanence: Environmental Politics in the United States, 1955–1985 (1987), the standard scholarly history

- Hays, Samuel P. A History of Environmental Politics since 1945 (2000), shorter standard history

- Hays, Samuel P. Conservation and the Gospel of Efficiency (1959), on Progressive Era.

- Herring, Hall and Thomas McIntyre. "Hunting's New Ambassadors (Sporting Conservation Council) ". Field and Stream 111.2 (June 2006): p. 18.

- Judd, Richard W. Common Lands and Common People, The Origins of Conservation in Northern New England (1997)

- King, Judson. The Conservation Fight, From Theodore Roosevelt to the Tennessee Valley Authority (2009)

- Merrill, Karen R. Public Lands and Political Meanings: Ranchers, the Government, and the Property between Them (2002).

- Nash, Roderick. Wilderness and the American Mind, (3rd ed. 1982), the standard intellectual history

- Pope, Carl. "A Sporting Chance – Sportsmen and Sportswomen are some of the biggest supporters for the preservation of wildlife". Sierra. 81.3 (May/June 1996): 14.

- Reiger, George. "Common Ground: Battles Over Hunting Only Draw Attention Away From the Real Threat to Wildlife". Field and Stream 100.2 (June 1985): p. 12.

- Reiger, George. "Sportsmen Get No Respect (Media Ignores Role of Sportsmen in Conservation) ". Field and Stream 101.10 (Feb 1997): p. 18.

- Rome, Adam. Bulldozer in the Countryside: Suburban Sprawl and the Rise of American Environmentalism (2001)

- Rothman, Hal K. The Greening of a Nation? Environmentalism in the United States since 1945 (1998)

- Scheffer, Victor B. The Shaping of Environmentalism in America (1991).

- Short, C. Brant. Ronald Reagan and the Public Lands: America's Conservation Debate (1989).

- Strong, Douglas H. Dreamers & Defenders: American Conservationists. (1988) online edition, good biographical studies of the major leaders

- Turner, James Morton, "The Specter of Environmentalism": Wilderness, Environmental Politics, and the Evolution of the New Right. The Journal of American History 96.1 (2009): 123-47 online at History Cooperative

- Van Liere, Kent D., and Riley E. Dunlap. "The Social Bases of Environmental Concern: A Review of Hypotheses, Explanations and Empirical Evidence," Public Opinion Quarterly 44:181-197 (1980)

[edit] External links

- A Lot To Say – Spreading Environmentally Positive Messages Through Organic Clothing

- The Everglades in the Time of Marjorie Stoneman Douglas Photo exhibit created by the State Archives of Florida

- British Virgin Islands Conservation Coral Reef Disaster Documentary This documentary exposes the challenges facing the Islanders who are battling the government to curtail this development disaster.

- A history of conservation in New Zealand

- For Future Generations, a Canadian documentary on conservation and national parks

- Amazon Rainforest Fund