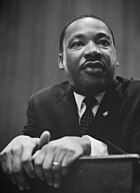

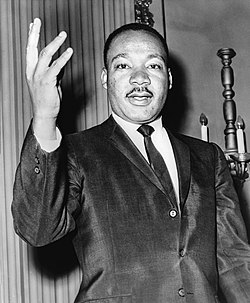

Martin Luther King, Jr.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Martin Luther King, Jr. | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Date of birth: | January 15, 1929(1929-01-15) |

| Place of birth: | Atlanta, Georgia, United States |

| Date of death: | April 4, 1968 (aged 39) |

| Place of death: | Memphis, Tennessee, United States |

| Movement: | African-American Civil Rights Movement and Peace movement |

| Major organizations: | Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) |

| Notable prizes: | Nobel Peace Prize (1964) Presidential Medal of Freedom (1977, posthumous) Congressional Gold Medal (2004, posthumous) |

| Major monuments: | Martin Luther King, Jr. National Memorial (planned) |

| Alma mater: | Morehouse College Crozer Theological Seminary Boston University |

| Religion: | Baptist |

| Influences | Abraham Lincoln, Mahatma Gandhi, Benjamin Mays, Hosea Williams, Rosa Parks, Bayard Rustin, Henry David Thoreau, Howard Thurman, Leo Tolstoy |

| Influenced | Albert Lutuli, Jesse Jackson, Al Sharpton, Barack Obama |

Martin Luther King, Jr. (January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American clergyman, activist and prominent leader in the African-American civil rights movement. His main legacy was to secure progress on civil rights in the United States and he is frequently referenced as a human rights icon today.

A Baptist minister,[1] King became a civil rights activist early in his career. He led the 1955 Montgomery Bus Boycott and helped found the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in 1957, serving as its first president.

King's efforts led to the 1963 March on Washington, where King delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech. There, he raised public consciousness of the civil rights movement and established himself as one of the greatest orators in U.S. history.

In 1964, King became the youngest person to receive the Nobel Peace Prize for his work to end racial segregation and racial discrimination through civil disobedience and other non-violent means. By the time of his death in 1968, he had refocused his efforts on ending poverty and opposing the Vietnam War, both from a religious perspective.

King was assassinated on April 4, 1968, in Memphis, Tennessee. He was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1977 and Congressional Gold Medal in 2004; Martin Luther King, Jr. Day was established as a U.S. national holiday in 1986.

Early life

Martin Luther King, Jr., was born on January 15, 1929, in Atlanta, Georgia. He was the son of the Reverend Martin Luther King, Sr. and Alberta Williams King.[2] King's father was born "Michael King", and Martin Luther King, Jr., was originally named "Michael King, Jr.", until the family traveled to Europe in 1934 and visited Germany. His father soon changed both of their names to Martin in honor of the German Protestant leader Martin Luther.[3] He had an older sister, Willie Christine King, and a younger brother Alfred Daniel Williams King.[4] King sang with his church choir at the 1939 Atlanta premiere of the movie Gone with the Wind.[5]

Growing up in Atlanta, King attended Booker T. Washington High School. He skipped ninth and twelfth grade, and entered Morehouse College at age fifteen without formally graduating from high school.[6] In 1948, he graduated from Morehouse with a Bachelor of Arts degree in sociology,[7] and enrolled in Crozer Theological Seminary in Chester, Pennsylvania, from which he graduated with a Bachelor of Divinity degree in 1951.[8] King then began doctoral studies in systematic theology at Boston University and received his Doctor of Philosophy on June 5, 1955. A 1980s inquiry concluded portions of his dissertation had been plagiarized and he had acted improperly but that his dissertation still "makes an intelligent contribution to scholarship".[9][10]

King married Coretta Scott, on June 18, 1953, on the lawn of her parents' house in her hometown of Heiberger, Alabama.[11] King and Scott had four children; Yolanda King, Martin Luther King III, Dexter Scott King, and Bernice King.[12] King became pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama when he was twenty-five years old in 1954.[13]

Influences

Populist tradition and Black populism

Harry C. Boyte, a self-proclaimed populist, field secretary of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and white civil rights activist describes an episode in his life that gives insight on King's influences:

My first encounter with deeper meanings of populism came when I was nineteen, working as a field secretary for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) in St. Augustine, Florida in 1964. One day I was caught by five men and a woman who were members of the Klu Klux Klan. They accused me of being a “communist and a Yankee.” I replied, “I’m no Yankee – my family has been in the South since before the Revolution. And I’m not a communist. I’m a populist. I believe that blacks and poor whites should join to do something about the big shots who keep us divided.” For a few minutes we talked about what such a movement might look like. Then they let me go.

When he learned of the incident, Martin Luther King, head of SCLC, told me that he identified with the populist tradition and assigned me to organize poor whites.[14]

Thurman

Civil rights leader, theologian, and educator Howard Thurman was an early influence on King. A classmate of King's father at Morehouse College,[15] Thurman mentored the young King and his friends.[16] Thurman's missionary work had taken him abroad where he had met and conferred with Gandhi.[17] When he was a student at Boston University, King often visited Thurman, who was the dean of Marsh Chapel.[18] Walter Fluker, who has studied Thurman's writings, has stated, "I don't believe you'd get a Martin Luther King, Jr. without a Howard Thurman".[19]

Gandhi and Rustin

Inspired by Gandhi's success with non-violent activism, King visited the Gandhi family in India in 1959, with assistance from the Quaker group the American Friends Service Committee.[20] The trip to India affected King in a profound way, deepening his understanding of non-violent resistance and his commitment to America’s struggle for civil rights. In a radio address made during his final evening in India, King reflected, “Since being in India, I am more convinced than ever before that the method of nonviolent resistance is the most potent weapon available to oppressed people in their struggle for justice and human dignity. In a real sense, Mahatma Gandhi embodied in his life certain universal principles that are inherent in the moral structure of the universe, and these principles are as inescapable as the law of gravitation.”[21] African American civil rights activist Bayard Rustin, who had studied Gandhi's teachings,[22] counseled King to dedicate himself to the principles of non-violence,[23] served as King's main advisor and mentor throughout his early activism,[24] and was the main organizer of the 1963 March on Washington.[25] Rustin's open homosexuality, support of democratic socialism, and his former ties to the Communist Party USA caused many white and African-American leaders to demand King distance himself from Rustin.[26]

Delivering the message

Throughout his career of service, King wrote and spoke frequently, drawing on his experience as a preacher. His "Letter from Birmingham Jail", written in 1963, is a "passionate" statement of his crusade for justice.[27] On October 14, 1964, King became the youngest recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize, which was awarded to him for leading non-violent resistance to end racial prejudice in the United States.[28]

Montgomery Bus Boycott, 1955

In March 1955, a fifteen-year-old school girl, Claudette Colvin, refused to give up her bus seat to a white man in compliance with the Jim Crow laws. King was on the committee from the Birmingham African-American community that looked into the case; Edgar Nixon and Clifford Durr decided to wait for a better case to pursue.[29] On December 1, 1955, Rosa Parks was arrested for refusing to give up her seat.[30] The Montgomery Bus Boycott, urged and planned by Nixon and led by King, soon followed.[31] The boycott lasted for 385 days,[32] and the situation became so tense that King's house was bombed.[33] King was arrested during this campaign, which ended with a United States District Court ruling in Browder v. Gayle that ended racial segregation on all Montgomery public buses.[34]

Southern Christian Leadership Conference

In 1957, King, Ralph Abernathy, and other civil rights activists founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). The group was created to harness the moral authority and organizing power of black churches to conduct non-violent protests in the service of civil rights reform. King led the SCLC until his death.[35] In 1958, while signing copies of his book Strive Toward Freedom in a Harlem department store, he was stabbed in the chest by Izola Curry, a deranged black woman with a letter opener, and narrowly escaped death.[36]

Gandhi's nonviolent techniques were useful to King's campaign to correct the civil rights laws implemented in Alabama.[37] King applied non-violent philosophy to the protests organized by the SCLC. In 1959, he wrote The Measure of A Man, from which the piece What is Man?, an attempt to sketch the optimal political, social, and economic structure of society, is derived.[38] His SCLC secretary and personal assistant in this period was Dora McDonald.

The FBI, under written directive from then Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, began telephone tapping King in 1963.[39] J. Edgar Hoover feared Communists were trying to infiltrate the Civil Rights Movement, but when no such evidence emerged, the bureau used the incidental details caught on tape over the next five years in attempts to force King out of the preeminent leadership position.[40]

King believed that organized, nonviolent protest against the system of southern segregation known as Jim Crow laws would lead to extensive media coverage of the struggle for black equality and voting rights. Journalistic accounts and televised footage of the daily deprivation and indignities suffered by southern blacks, and of segregationist violence and harassment of civil rights workers and marchers, produced a wave of sympathetic public opinion that convinced the majority of Americans that the Civil Rights Movement was the most important issue in American politics in the early 1960s.[41]

King organized and led marches for blacks' right to vote, desegregation, labor rights and other basic civil rights.[42] Most of these rights were successfully enacted into the law of the United States with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the 1965 Voting Rights Act.[43]

King and the SCLC applied the principles of nonviolent protest with great success by strategically choosing the method of protest and the places in which protests were carried out. There were often dramatic stand-offs with segregationist authorities. Sometimes these confrontations turned violent.[44]

Albany movement

The Albany Movement was a desegregation coalition formed in Albany, Georgia in November, 1961. In December King and the SCLC became involved. The movement mobilized thousands of citizens for a broad-front nonviolent attack on every aspect of segregation within the city and attracted nationwide attention. When King first visited on December 15, 1961, he "had planned to stay a day or so and return home after giving counsel."[45] But the following day he was swept up in a mass arrest of peaceful demonstrators, and he declined bail until the city made concessions. "Those agreements", said King, "were dishonored and violated by the city," as soon as he left town.[45] King returned in July 1962, and was sentenced to forty-five days in jail or a $178 fine. He chose jail. Three days into his sentence, Chief Pritchett discreetly arranged for King's fine to be paid and ordered his release. "We had witnessed persons being kicked off lunch counter stools ... ejected from churches ... and thrown into jail ... But for the first time, we witnessed being kicked out of jail."[45]

After nearly a year of intense activism with few tangible results, the movement began to deteriorate. King requested a halt to all demonstrations and a "Day of Penance" to promote non-violence and maintain the moral high ground. Divisions within the black community and the canny, low-key response by local government defeated efforts.[46] However, it was credited as a key lesson in tactics for the national civil rights movement.[47]

Birmingham campaign

The Birmingham campaign was a strategic effort by the SCLC to promote civil rights for African Americans. Many of its tactics of "Project C" were developed by Rev. Wyatt Tee Walker, Executive Director of SCLC from 1960-1964. Based on actions in Birmingham, Alabama, its goal was to end the city's segregated civil and discriminatory economic policies. The campaign lasted for more than two months in the spring of 1963. To provoke the police into filling the city's jails to overflowing, King and black citizens of Birmingham employed nonviolent tactics to flout laws they considered unfair. King summarized the philosophy of the Birmingham campaign when he said, "The purpose of ... direct action is to create a situation so crisis-packed that it will inevitably open the door to negotiation".[48]

Protests in Birmingham began with a boycott to pressure businesses to sales jobs and other employment to people of all races, as well as to end segregated facilities in the stores. When business leaders resisted the boycott, King and the SCLC began what they termed Project C, a series of sit-ins and marches intended to provoke arrest. After the campaign ran low on adult volunteers, it recruited children for what became known as the "Children's Crusade". During the protests, the Birmingham Police Department, led by Eugene "Bull" Connor, used high-pressure water jets and police dogs to control protesters, including children. Not all of the demonstrators were peaceful, despite the avowed intentions of the SCLC. In some cases, bystanders attacked the police, who responded with force. King and the SCLC were criticized for putting children in harm's way. By the end of the campaign, King's reputation improved immensely, Connor lost his job, the "Jim Crow" signs in Birmingham came down, and public places became more open to blacks.[49]

Augustine and Selma

King and SCLC were also driving forces behind the protest in St. Augustine, Florida, in 1964.[50] The movement engaged in nightly marches in the city met by white segregationists who violently assaulted them. Hundreds of the marchers were arrested and jailed.

King and the SCLC joined forces with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in Selma, Alabama, in December 1964, where SNCC had been working on voter registration for several months.[51] A sweeping injunction issued by a local judge barred any gathering of 3 or more people under sponsorship of SNCC, SCLC, or DCVL, or with the involvement of 41 named civil rights leaders. This injunction temporarily halted civil rights activity until King defied it by speaking at Brown Chapel on January 2 1965.[52]

March on Washington, 1963

King, representing SCLC, was among the leaders of the so-called "Big Six" civil rights organizations who were instrumental in the organization of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963. The other leaders and organizations comprising the Big Six were: Roy Wilkins from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People; Whitney Young, National Urban League; A. Philip Randolph, Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters; John Lewis, SNCC; and James L. Farmer, Jr. of the Congress of Racial Equality.[53] The primary logistical and strategic organizer was King's colleague Bayard Rustin.[54] For King, this role was another which courted controversy, since he was one of the key figures who acceded to the wishes of President John F. Kennedy in changing the focus of the march.[55] Kennedy initially opposed the march outright, because he was concerned it would negatively impact the drive for passage of civil rights legislation, but the organizers were firm that the march would proceed.[56]

The march originally was conceived as an event to dramatize the desperate condition of blacks in the southern United States and a very public opportunity to place organizers' concerns and grievances squarely before the seat of power in the nation's capital. Organizers intended to excoriate and then challenge the federal government for its failure to safeguard the civil rights and physical safety of civil rights workers and blacks, generally, in the South. However, the group acquiesced to presidential pressure and influence, and the event ultimately took on a far less strident tone.[57] As a result, some civil rights activists felt it presented an inaccurate, sanitized pageant of racial harmony; Malcolm X called it the "Farce on Washington," and members of the Nation of Islam were not permitted to attend the march.[57][58]

The march did, however, make specific demands: an end to racial segregation in public school; meaningful civil rights legislation, including a law prohibiting racial discrimination in employment; protection of civil rights workers from police brutality; a $2 minimum wage for all workers; and self-government for Washington, D.C., then governed by congressional committee.[59] Despite tensions, the march was a resounding success. More than a quarter million people of diverse ethnicities attended the event, sprawling from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial onto the National Mall and around the reflecting pool. At the time, it was the largest gathering of protesters in Washington's history.[60] King's "I Have a Dream" speech electrified the crowd. It is regarded, along with Abraham Lincoln's Gettysburg Address and Franklin D. Roosevelt's Infamy Speech, as one of the finest speeches in the history of American oratory.[61]

Stance on compensation

Martin Luther King Jr. expressed a view that black Americans, as well as other disadvantaged Americans, should be compensated for historical wrongs. In an interview conducted for Playboy in 1965, he said that granting black Americans only equality could not realistically close the economic gap between them and whites. King said that he did not seek a full restitution of wages lost to slavery, which he believed impossible, but proposed a government compensatory program of US$50 billion over ten years to all disadvantaged groups. He posited that "the money spent would be more than amply justified by the benefits that would accrue to the nation through a spectacular decline in school dropouts, family breakups, crime rates, illegitimacy, swollen relief rolls, rioting and other social evils".[62] He presented this idea as an application of the common law regarding settlement of unpaid labor but clarified that he felt that the money should not be spent exclusively on blacks. He stated, "It should benefit the disadvantaged of all races".[63]

"Bloody Sunday", 1965

King and SCLC, in partial collaboration with SNCC, attempted to organize a march from Selma to the state capital of Montgomery, for March 7, 1965. The first attempt to march on March 7 was aborted because of mob and police violence against the demonstrators. This day has since become known as Bloody Sunday. Bloody Sunday was a major turning point in the effort to gain public support for the Civil Rights Movement, the clearest demonstration up to that time of the dramatic potential of King's nonviolence strategy. King, however, was not present. After meeting with President Lyndon B. Johnson, he decided not to endorse the march, but it was carried out against his wishes and without his presence on March 7 by local civil rights leaders. Footage of police brutality against the protesters was broadcast extensively and aroused national public outrage.[64]

King next attempted to organize a march for March 9. The SCLC petitioned for an injunction in federal court against the State of Alabama; this was denied and the judge issued an order blocking the march until after a hearing. Nonetheless, King led marchers on March 9 to the Edmund Pettus bridge, then held a short prayer session before turning the marchers around and asking them to disperse so as not to violate the court order. The unexpected ending of this second march aroused the surprise and anger of many within the local movement.[65] The march finally went ahead fully on March 25.[66] At the conclusion of the march and on the steps of the state capitol, King delivered a speech that has become known as "How Long, Not Long".[67]

Chicago, 1966

In 1966, after several successes in the South, King and others in the civil rights organizations tried to spread the movement to the North, with Chicago as its first destination. King and Ralph Abernathy, both from the middle classes, moved into the slums of North Lawndale[68] on the west side of Chicago as an educational experience and to demonstrate their support and empathy for the poor.[69]

The SCLC formed a coalition with CCCO, Coordinating Council of Community Organizations, an organization founded by Albert Raby, and the combined organizations' efforts were fostered under the aegis of The Chicago Freedom Movement.[70] During that spring, several dual white couple/black couple tests on real estate offices uncovered the practice (now banned in the U.S.) of racial steering. These tests revealed the racially selective processing of housing requests by couples who were exact matches in income, background, number of children, and other attributes, with the only difference being their race.[71]

The needs of the movement for radical change grew, and several larger marches were planned and executed, including those in the following neighborhoods: Bogan, Belmont Cragin, Jefferson Park, Evergreen Park (a suburb southwest of Chicago), Gage Park and Marquette Park, among others.[72]

In Chicago, Abernathy later wrote that they received a worse reception than they had in the South. Their marches were met by thrown bottles and screaming throngs, and they were truly afraid of starting a riot.[73] King's beliefs mitigated against his staging a violent event, and he negotiated an agreement with Mayor Richard J. Daley to cancel a march in order to avoid the violence that he feared would result from the demonstration.[74] King, who received death threats throughout his involvement in the civil rights movement, was hit by a brick during one march but continued to lead marches in the face of personal danger.[75]

When King and his allies returned to the south, they left Jesse Jackson, a seminary student who had previously joined the movement in the South, in charge of their organization.[76] Jackson continued their struggle for civil rights by organizing the Operation Breadbasket movement that targeted chain stores that did not deal fairly with blacks.[77]

Opposition to the Vietnam War

Starting in 1965, King began to express doubts about the United States' role in the Vietnam War. In an April 4, 1967 appearance at the New York City Riverside Church—exactly one year before his death—King delivered a speech titled "Beyond Vietnam".[78] In the speech, he spoke strongly against the U.S.'s role in the war, insisting that the U.S. was in Vietnam "to occupy it as an American colony"[79] and calling the U.S. government "the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today".[80] He also argued that the country needed larger and broader moral changes:

A true revolution of values will soon look uneasily on the glaring contrast of poverty and wealth. With righteous indignation, it will look across the seas and see individual capitalists of the West investing huge sums of money in Asia, Africa and South America, only to take the profits out with no concern for the social betterment of the countries, and say: "This is not just."[81]

King also was opposed to the Vietnam War on the grounds that the war took money and resources that could have been spent on social welfare services like the War on Poverty. The United States Congress was spending more and more on the military and less and less on anti-poverty programs at the same time. He summed up this aspect by saying, "A nation that continues year after year to spend more money on military defense than on programs of social uplift is approaching spiritual death".[81]

Many white southern segregationists vilified King; moreover, this speech soured his relationship with many members of the mainstream media. Life magazine called the speech "demagogic slander that sounded like a script for Radio Hanoi",[78] and The Washington Post declared that King had "diminished his usefulness to his cause, his country, his people."[82]

King stated that North Vietnam "did not begin to send in any large number of supplies or men until American forces had arrived in the tens of thousands".[83] King also criticized the United States' resistance to North Vietnam's land reforms.[84] He accused the United States of having killed a million Vietnamese, "mostly children."[85]

The speech was a reflection of King's evolving political advocacy in his later years, which paralleled the teachings of the progressive Highlander Research and Education Center, with whom King was affiliated.[86] King began to speak of the need for fundamental changes in the political and economic life of the nation. Toward the end of his life, King more frequently expressed his opposition to the war and his desire to see a redistribution of resources to correct racial and economic injustice.[87] Though his public language was guarded, so as to avoid being linked to communism by his political enemies, in private he sometimes spoke of his support for democratic socialism. In one speech, he stated that "something is wrong with capitalism" and claimed, "There must be a better distribution of wealth, and maybe America must move toward a democratic socialism."[88]

King had read Marx while at Morehouse, but while he rejected "traditional capitalism," he also rejected Communism because of its "materialistic interpretation of history" that denied religion, its "ethical relativism," and its "political totalitarianism."[89]

King also stated in his "Beyond Vietnam" speech that "true compassion is more than flinging a coin to a beggar....it comes to see that an edifice which produces beggars needs restructuring".[90] King quoted a United States official, who said that, from Vietnam to South America to Latin America, the country was "on the wrong side of a world revolution"[90] King condemned America's "alliance with the landed gentry of Latin America," and said that the United States should support "the shirtless and barefoot people" in the Third World rather than suppressing their attempts at revolution.[91]

Poor People's Campaign, 1968

In 1968, King and the SCLC organized the "Poor People's Campaign" to address issues of economic justice. The campaign culminated in a march on Washington, D.C. demanding economic aid to the poorest communities of the United States. King traveled the country to assemble "a multiracial army of the poor" that would march on Washington to engage in nonviolent civil disobedience at the Capitol until Congress created a bill of rights for poor Americans.[92][93]

However, the campaign was not unanimously supported by other leaders of the Civil Rights Movement. Rustin resigned from the march stating that the goals of the campaign were too broad, the demands unrealizable, and thought these campaigns would accelerate the backlash and repression on the poor and the black.[94] Throughout his participation in the civil rights movement, King was criticized by many groups. This included opposition by more militant blacks and such prominent critics as Nation of Islam member Malcolm X.[95]Stokely Carmichael was a separatist and disagreed with King's plea for racial integration because he considered it an insult to a uniquely African-American culture.[96]Omali Yeshitela urged Africans to remember the history of violent European colonization and how power was not secured by Europeans through integration, but by violence and force.[97]

King and the SCLC called on the government to invest in rebuilding America's cities. He felt that Congress had shown "hostility to the poor" by spending "military funds with alacrity and generosity". He contrasted this with the situation faced by poor Americans, claiming that Congress had merely provided "poverty funds with miserliness".[93] His vision was for change that was more revolutionary than mere reform: he cited systematic flaws of "racism, poverty, militarism and materialism", and argued that "reconstruction of society itself is the real issue to be faced".[98]

Assassination

On March 29, 1968, King went to Memphis, Tennessee in support of the black sanitary public works employees, represented by AFSCME Local 1733, who had been on strike since March 12 for higher wages and better treatment. In one incident, black street repairmen received pay for two hours when they were sent home because of bad weather, but white employees were paid for the full day.[99][100]

On April 3, King addressed a rally and delivered his "I've Been to the Mountaintop" address at Mason Temple, the World Headquarters of the Church of God in Christ. King's flight to Memphis had been delayed by a bomb threat against his plane.[101] In the close of the last speech of his career, in reference to the bomb threat, King said the following:

And then I got to Memphis. And some began to say the threats, or talk about the threats that were out. What would happen to me from some of our sick white brothers? Well, I don't know what will happen now. We've got some difficult days ahead. But it doesn't matter with me now. Because I've been to the mountaintop. And I don't mind. Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I'm not concerned about that now. I just want to do God's will. And He's allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I've looked over. And I've seen the promised land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the promised land. And I'm happy, tonight. I'm not worried about anything. I'm not fearing any man. Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord.[102]

King was booked in room 306 at the Lorraine Motel, owned by Walter Bailey, in Memphis. The Reverend Ralph Abernathy, King's close friend and colleague who was present at the assassination, swore under oath to the United States House Select Committee on Assassinations that King and his entourage stayed at room 306 at the Lorraine Motel so often it was known as the 'King-Abernathy suite.'[103] King was shot at 6:01 p.m. April 4, 1968 while he was standing on the motel's second floor balcony. The bullet entered through his right cheek smashing his jaw and then traveled down his spinal cord before lodging in his shoulder.[104] According to Jesse Jackson, who was present, King's last words on the balcony were to musician Ben Branch, who was scheduled to perform that night at an event King was attending: "Ben, make sure you play Take My Hand, Precious Lord in the meeting tonight. Play it real pretty."[105] Abernathy heard the shot from inside the motel room and ran to the balcony to find King on the floor.[106] The events following the shooting have been disputed, as some people have accused Jackson of exaggerating his response.[107]

After emergency surgery, King was pronounced dead at St. Joseph's Hospital at 7:05 p.m.[108] According to biographer Taylor Branch, King's autopsy revealed that though only thirty-nine years old, he had the heart of a sixty-year-old, perhaps a result of the stress of thirteen years in the civil rights movement.[109]

The assassination led to a nationwide wave of riots in more than 100 cities.[110] Presidential nominee Robert Kennedy was on his way to Indianapolis for a campaign rally when he was informed of King's death. He gave a short yet empowering speech to the gathering of supporters informing them of the tragedy and asking them to continue King's idea of non-violence.[111] President Lyndon B. Johnson declared April 7 a national day of mourning for the civil rights leader.[112] Vice-President Hubert Humphrey attended King's funeral on behalf of Lyndon B. Johnson, as there were fears that Johnson's presence might incite protests and perhaps violence.[113] At his widow's request, King's last sermon at Ebenezer Baptist Church was played at the funeral.[114] It was a recording of his "Drum Major" sermon, given on February 4, 1968. In that sermon, King made a request that at his funeral no mention of his awards and honors be made, but that it be said that he tried to "feed the hungry", "clothe the naked", "be right on the [Vietnam] war question", and "love and serve humanity".[115] His good friend Mahalia Jackson sang his favorite hymn, "Take My hand, Precious Lord", at the funeral.[116] The city of Memphis quickly settled the strike on terms favorable to the sanitation workers.[117][118]

Two months after King's death, escaped convict James Earl Ray was captured at London Heathrow Airport while trying to leave the United Kingdom on a false Canadian passport in the name of Ramon George Sneyd.[119] Ray was quickly extradited to Tennessee and charged with King's murder. He confessed to the assassination on March 10, 1969, though he recanted this confession three days later.[120] On the advice of his attorney Percy Foreman, Ray pleaded guilty to avoid a trial conviction and thus the possibility of receiving the death penalty. Ray was sentenced to a 99-year prison term.[120][121] Ray fired Foreman as his attorney, from then on derisively calling him "Percy Fourflusher".[122] He claimed a man he met in Montreal, Quebec with the alias "Raoul" was involved and that the assassination was the result of a conspiracy.[123][124] He spent the remainder of his life attempting (unsuccessfully) to withdraw his guilty plea and secure the trial he never had.[121] On June 10, 1977, shortly after Ray had testified to the House Select Committee on Assassinations that he did not shoot King, he and six other convicts escaped from Brushy Mountain State Penitentiary in Petros, Tennessee. They were recaptured on June 13 and returned to prison.[125]

Allegations of conspiracy

Ray's lawyers maintained he was a scapegoat similar to the way that alleged John F. Kennedy assassin Lee Harvey Oswald is seen by conspiracy theorists.[126] One of the claims used to support this assertion is that Ray's confession was given under pressure, and he had been threatened with the death penalty.[121][127] Ray was a thief and burglar, but he had no record of committing violent crimes with a weapon.[124]

Those suspecting a conspiracy in the assassination point out the two separate ballistics tests conducted on the Remington Gamemaster recovered by police had neither conclusively proved Ray had been the killer nor that it had even been the murder weapon.[121][128] Moreover, witnesses surrounding King at the moment of his death say the shot came from another location, from behind thick shrubbery near the rooming house - which had been inexplicably cut away in the days following the assassination - and not from the rooming house window.[129]

Developments

In 1997, King's son Dexter Scott King met with Ray, and publicly supported Ray's efforts to obtain a new trial.[130] Two years later, Coretta Scott King, King's widow, along with the rest of King's family, won a wrongful death claim against Loyd Jowers and "other unknown co-conspirators". Jowers claimed to have received $100,000 to arrange King's assassination. The jury of six whites and six blacks found Jowers guilty and that government agencies were party to the assassination.[131]William F. Pepper represented the King family in the trial.[132] King biographer David Garrow disagrees with William F. Pepper's claims that the government killed King.[133] He is supported by author Gerald Posner who has researched and written about the assassination.[134]

In 2000, the United States Department of Justice completed the investigation about Jowers' claims but did not find evidence to support allegations about conspiracy. The investigation report recommended no further investigation unless some new reliable facts are presented.[135]The New York Times reported a church minister, Rev. Ronald Denton Wilson, claimed his father, Henry Clay Wilson — not James Earl Ray — assassinated Martin Luther King, Jr. He stated, "It wasn't a racist thing; he thought Martin Luther King was connected with communism, and he wanted to get him out of the way."[136]

King's friend and colleague, James Bevel, disputed the argument that Ray acted alone, stating, "There is no way a ten-cent white boy could develop a plan to kill a million-dollar black man."[137] In 2004, Jesse Jackson, who was with King at the time of his death, noted:

The fact is there were saboteurs to disrupt the march. And within our own organization, we found a very key person who was on the government payroll. So infiltration within, saboteurs from without and the press attacks. …I will never believe that James Earl Ray had the motive, the money and the mobility to have done it himself. Our government was very involved in setting the stage for and I think the escape route for James Earl Ray.[138]

FBI and wiretapping

King had a mutually antagonistic relationship with the FBI, especially its director, J. Edgar Hoover.[139] The FBI began tracking King and the SCLC in 1957;[40] its investigations were largely superficial until 1962, when it learned that one of King's most trusted advisers was New York City lawyer Stanley Levison. The FBI found Levison had been involved with the Communist Party USA,[140] though the FBI considered him an inactive party member.[141] Another King lieutenant, Hunter Pitts O'Dell, was also linked to the Communist Party by sworn testimony before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC).[142] The Bureau placed wiretaps on Levison's and King's home and office phones, and bugged King's rooms in hotels as he traveled across the country.[143][144] The Bureau received authorization to proceed with wiretapping from Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy in 1963[145] and informed President John F. Kennedy, both of whom unsuccessfully tried to persuade King to dissociate himself from Levison.[143] For his part, King adamantly denied having any connections to Communism, stating in a 1965 Playboy interview that "there are as many Communists in this freedom movement as there are Eskimos in Florida";[146] Hoover did not believe the statement and replied by saying that King was "the most notorious liar in the country."[147] After King gave his "I Have A Dream" speech during the March on Washington on August 28, 1963, the FBI described King as "the most dangerous and effective Negro leader in the country".[144]

The attempt to prove that King was a Communist was in keeping with the feeling of many segregationists that blacks in the South were happy with their lot but had been stirred up by "communists" and "outside agitators".[148] Lawyer-advisor Stanley D. Levison did have ties with the Communist Party in various business dealings, but the FBI refused to believe its own intelligence bureau reports that Levison was no longer associated in that capacity.[149] In response to the FBI's comments regarding communists directing the civil rights movement, King said that "the Negro revolution is a genuine revolution, born from the same womb that produces all massive social upheavals—the womb of intolerable conditions and unendurable situations."[150]

Later, the focus of the Bureau's investigations shifted to attempting to discredit King through revelations regarding his private life. FBI surveillance of King, some of it since made public, attempted to demonstrate that he also engaged in numerous extramarital affairs.[144] Further remarks on King's lifestyle were made by several prominent officials, such as Lyndon Johnson, who once said that King was a “hypocritical preacher”.[151] One incident that caught the FBI's attention was purported recording of a sexual encounter that took place at a 1964 party King was attending at the Willard Hotel in Washington D.C.[144] The FBI presumed it was King who they heard engaged in a sexual encounter.[152]Ralph Abernathy, a close associate of King's, stated in his 1989 autobiography And the Walls Came Tumbling Down that King had a "weakness for women".[153][154] In a later interview, Abernathy said he only wrote the term "womanizing", and did not specifically say King had extramarital sex.[155] Arguments that King possibly engaged in sexual affairs have been detailed by history professor David Garrow.[156]

The FBI distributed reports regarding such affairs to the executive branch, friendly reporters, potential coalition partners and funding sources of the SCLC, and King's family.[157] The Bureau also sent anonymous letters to King threatening to reveal information if he did not cease his civil rights work.[158] One anonymous letter sent to King just before he received the Nobel Peace Prize read, in part, "The American public, the church organizations that have been helping—Protestants, Catholics and Jews will know you for what you are—an evil beast. So will others who have backed you. You are done. King, there, is only one thing left for you to do. You know what it is. You have just 34 days in which to do (this exact number has been selected for a specific reason, it has definite practical significant [sic]). You are done. There is but one way out for you. You better take it before your filthy fraudulent self is bared to the nation."[159] King interpreted this as encouragement for him to commit suicide,[160] although William Sullivan, head of the Domestic Intelligence Division at the time, argued that it may have only been intended to "convince Dr. King to resign from the SCLC."[161] King refused to give in to the FBI's threats.[152]

In January 31, 1977, United States district Judge John Lewis Smith, Jr., ordered all known copies of the recorded audiotapes and written transcripts resulting from the FBI's electronic surveillance of King between 1963 and 1968 to be held in the National Archives and sealed from public access until 2027.[162]

Across from the Lorraine Motel, next to the rooming house in which James Earl Ray was staying, was a fire station. Police officers were stationed in the fire station to keep King under surveillance.[163] Using papered-over windows with peepholes cut into them, the agents were watching the scene while Martin Luther King was shot.[164] Immediately following the shooting, officers rushed out of the station to the motel, and Marrell McCollough, an undercover police officer, was the first person to administer first-aid to King.[165] The antagonism between King and the FBI, the lack of an all points bulletin to find the killer, and the police presence nearby have led to speculation that the FBI was involved in the assassination.[166]

Legacy

King's main legacy was to secure progress on civil rights in the United States, which has enabled more Americans to reach their potential. He is frequently referenced as a human rights icon today. His name and legacy have often been invoked since his death as people have debated his likely position on various modern political issues.

On the international scene, King's legacy included influences on the Black Consciousness Movement and Civil Rights Movement in South Africa.[167] King's work was cited by and served as an inspiration for Albert Lutuli, another black Nobel Peace prize winner who fought for racial justice in that country.[168] The day following King's assassination, school teacher Jane Elliott conducted her first "Blue Eyes/Brown Eyes" exercise with her class of elementary school students in Riceville, Iowa. Her purpose was to help them understand King's death as it related to racism, something they little understood from having lived in a predominately white community.[169]

King's wife, Coretta Scott King, followed her husband's footsteps and was active in matters of social justice and civil rights until her death in 2006. The same year that Martin Luther King was assassinated, Mrs. King established the King Center in Atlanta, Georgia, dedicated to preserving his legacy and the work of championing nonviolent conflict resolution and tolerance worldwide.[170] His son, Dexter King, currently serves as the center's chairman.[171] Daughter Yolanda King is a motivational speaker, author and founder of Higher Ground Productions, an organization specializing in diversity training.[172]

There are opposing views even within the King family — regarding the slain civil rights leader's religious and political views about homosexuals, lesbians, bisexuals and transgendered people. King's widow Coretta said publicly that she believed her husband would have supported gay rights. However, his daughter Bernice believed he would have been opposed to them.[173] The King Center includes discrimination, and lists homophobia as one of its examples, in its list of "The Triple Evils" that should be opposed.[174]

In 1980, the Department of Interior designated King's boyhood home in Atlanta and several nearby buildings the Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site. In 1996, United States Congress authorized the Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity to establish a foundation to manage fund raising and design of a Martin Luther King, Jr. National Memorial on the Mall in Washington, DC.[175] King was a member of Alpha Phi Alpha, the first intercollegiate Greek-letter fraternity established by and for African Americans.[176] King was the first African American honored with his own memorial in the National Mall area and the first non-President to be commemorated in such a way.[177] The sculptor chosen was Lei Yixin.[178] The King Memorial will be administered by the National Park Service.[179]

King's life and assassination inspired many artistic works. In 1969 Maya Angelou published her autobiography I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings.[180] In spring of 2006, a stage play about King was produced in Beijing, China with King portrayed by Chinese actor, Cao Li. The play was written by Stanford University professor, Clayborne Carson.[181]

Martin Luther King Jr. Day

At the White House Rose Garden on November 2, 1983, President Ronald Reagan signed a bill creating a federal holiday to honor King. Observed for the first time on January 20, 1986, it is called Martin Luther King, Jr. Day. Following President George H. W. Bush's 1992 proclamation, the holiday is observed on the third Monday of January each year, near the time of King's birthday.[182] On January 17, 2000, for the first time, Martin Luther King Jr. Day was officially observed in all fifty U.S. states.[183]

Awards and recognition

King was awarded at least fifty honorary degrees from colleges and universities in the U.S. and elsewhere.[184][9] Besides winning the 1964 Nobel Peace Prize, in 1965 King was awarded the American Liberties Medallion by the American Jewish Committee for his "exceptional advancement of the principles of human liberty".[184][185] Reverend King said in his acceptance remarks, "Freedom is one thing. You have it all or you are not free".[186] King was also awarded the Pacem in Terris Award, named after a 1963 encyclical letter by Pope John XXIII calling for all people to strive for peace.[187]

In 1966, the Planned Parenthood Federation of America awarded King the Margaret Sanger Award for "his courageous resistance to bigotry and his lifelong dedication to the advancement of social justice and human dignity."[188] King was posthumously awarded the Marcus Garvey Prize for Human Rights by Jamaica in 1968.[9]

In 1971, King was posthumously awarded the Grammy Award for Best Spoken Word Album for his Why I Oppose the War in Vietnam.[189] Six years later, the Presidential Medal of Freedom was awarded to King by Jimmy Carter.[190] King and his wife were also awarded the Congressional Gold Medal in 2004.[191]

King was second in Gallup's List of Widely Admired People in the 20th century.[192] In 1963 King was named Time Person of the Year and in 2000, King was voted sixth in the Person of the Century poll by the same magazine.[193] King was elected third in the Greatest American contest conducted by the Discovery Channel and AOL.[194]

More than 730 cities in the United States have streets named after King.[195]King County, Washington rededicated its name in his honor in 1986, and changed its logo to an image of his face in 2007.[196] The city government center in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, is named in honor of King.[197] King is venerated as a saint by the Episcopal Church in the United States of America (feast day April 4)[198] and the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (feast day January 15).[199]

In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante listed Martin Luther King, Jr. on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.[200]

See also

- Anti-racism

- Black Nobel Prize laureates

- Christian left

- Civil disobedience

- Civil rights leaders

- Congressional Gold Medal recipients

- List of notable African Americans

- List of pacifists

- List of religious leaders

- Nobel Peace Prize Laureates

- Nonviolent resistance

- Opposition to the Vietnam War

- Pacifism

- Racism in the United States

- Protest marches on Washington, DC

- Speeches by Martin Luther King, Jr.

Notes

- ^ Lischer, Richard. (2001). The Preacher King, p. 3.

- ^ Ogletree, Charles J. (2004). All Deliberate Speed: Reflections on the First Half Century of Brown v. Board of Education. W.W. Norton & Company. pp. 138. ISBN 0393058972.

- ^ Ling, Peter J. (2002). Martin Luther King, Jr.. Routledge. pp. 11. ISBN 0415216648.

- ^ King, Jr., Martin Luther; Clayborne Carson; Peter Holloran; Ralph Luker; Penny A. Russell (1992). The papers of Martin Luther King, Jr.. University of California Press. pp. 76. ISBN 0520079507.

- ^ Katznelson, Ira (2005). When Affirmative Action was White: An Untold History of Racial Inequality in Twentieth-Century America. W.W. Norton & Company. pp. 5. ISBN 0393052133.

- ^ Ching, Jacqueline (2002). The Assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr.. Rosen Publishing Group. pp. 18. ISBN 0823935434.

- ^ Downing, Frederick L. (1986). To See the Promised Land: The Faith Pilgrimage of Martin Luther King, Jr. Mercer University Press. pp. 150. ISBN 0865542074.

- ^ Nojeim, Michael J. (2004). Gandhi and King: The Power of Nonviolent Resistance. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 179. ISBN 0275965740.

- ^ a b c "Biographical Outline of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.". The King Center. http://www.thekingcenter.org/mlk/bio.html. Retrieved on 2008-06-08.

- ^ See Martin Luther King, Jr. authorship issues. See also: Baldwin, Lewis V. (1992). To Make the Wounded Whole: The Cultural Legacy of Martin Luther King, Jr.. Fortress Press. pp. 298. ISBN 0800625439. , "Boston U. Panel Finds Plagiarism by Dr. King". The New York Times. 1991-10-11. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9D0CEFD61030F932A25753C1A967958260. Retrieved on 2008-06-14. , Heller, Steven; Veronique Vienne (2003). Citizen Designer: Perspectives on Design Responsibility. Allworth Communications, Inc.. pp. 156. ISBN 1581152655.

- ^ "Coretta Scott King". Daily Telegraph. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/obituaries/1509338/Coretta-Scott-King.html. Retrieved on 2008-09-08.

- ^ Warren, Mervyn A. (2001). King Came Preaching: The Pulpit Power of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.. InterVarsity Press. pp. 35. ISBN 0830826580.

- ^ Fuller, Linda K. (2004). National Days/National Ways: Historical, Political, And Religious Celebrations around the World. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 314. ISBN 0275972704.

- ^ http://ginsberg.umich.edu/downloads/Boyte_Dewey_Lecture2007.doc

- ^ Thurman, Howard (1981). With Head and Heart: The Autobiography of Howard Thurman. Harcourt. pp. 254. ISBN 015697648X.

- ^ Thurman, Howard; Walter E. Fluker; Catherine Tumber (1998). A Strange Freedom: The Best of Howard Thurman on Religious Experience and Public Life. Beacon Press. pp. 6. ISBN 080701057X.

- ^ Curtis, Nancy C. (1996). Black Heritage Sites: An African American Odyssey and Finder's Guide. ALA Editions. pp. 62. ISBN 0838906435.

- ^ Marsh, Charles (1999). God's Long Summer: Stories of Faith and Civil Rights. Princeton University Press. pp. 122. ISBN 0691029407.

- ^ "The Legacy of Howard Thurman - Mystic and Theologian". Religion & Ethics Newsweekly. PBS. 2002-01-18. http://www.pbs.org/wnet/religionandethics/week520/feature.html. Retrieved on 2008-08-27.

- ^ King, Jr., Martin Luther; Clayborne Carson; Peter Holloran; Ralph Luker; Penny A. Russell (1992). The papers of Martin Luther King, Jr.. University of California Press. pp. 3. ISBN 0520079507.

- ^ King, Jr., Martin Luther; Clayborne Carson; Peter Holloran; Ralph Luker; Penny A. Russell (1992). The papers of Martin Luther King, Jr.. University of California Press. pp. 135–136. ISBN 0520079507.

- ^ Kahlenberg, Richard D.. "Book Review: Bayard Rustin: Troubles I've Seen". Washington Monthly. http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m1316/is_n4_v29/ai_19279952. Retrieved on 2008-06-12.

- ^ Bennett, Scott H. (2003). Radical Pacifism: The War Resisters League and Gandhian Nonviolence in America, 1915-1963. Syracuse University Press. pp. 217. ISBN 0815630034.

- ^ Farrell, James J. (1997). The Spirit of the Sixties: Making Postwar Radicalism. Routledge. pp. 90. ISBN 0415913853.

- ^ De Leon, David (1994). Leaders from the 1960s: a biographical sourcebook of American activism. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 138. ISBN 0313274142.

- ^ Arsenault, Raymond (2006). Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice. Oxford University Press US. pp. 62. ISBN 0195136748.

- ^ Galchutt, Kathryn M. (2005). The Career of Andrew Schulze, 1924-1968: Lutherans And Race in the Civil Rights Era. Mercer University Press. pp. 194. ISBN 086554946X.

- ^ Wintle, Justin (2001). Makers of Modern Culture: Makers of Culture. Routledge. pp. 272. ISBN 0415265835.

- ^ Manheimer, Ann S. (2004). Martin Luther King Jr: Dreaming of Equality. Twenty-First Century Books. pp. 103. ISBN 1575056275.

- ^ "December 1, 1955: Rosa Parks arrested". CNN. 2003-03-11. http://www.cnn.com/2003/US/03/10/sprj.80.1955.parks/index.html. Retrieved on 2008-06-08.

- ^ Walsh, Frank (2003). The Montgomery Bus Boycott. Gareth Stevens. pp. 24. ISBN 0836854039.

- ^ McMahon, Thomas F. (2004). Ethical Leadership Through Transforming Justice. University Press of America. pp. 25. ISBN 0761829083.

- ^ Fisk, Larry J.; John Schellenberg (1999). Patterns of Conflict, Paths to Peace. Broadview Press. pp. 115. ISBN 1551111543.

- ^ King, Jr., Martin Luther; Clayborne Carson; Peter Holloran; Ralph Luker; Penny A. Russell (1992). The papers of Martin Luther King, Jr.. University of California Press. pp. 9. ISBN 0520079507. See also: Jackson, Thomas F. (2007). From Civil Rights to Human Rights: Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Struggle for Economic Justice. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 53. ISBN 0812239695.

- ^ Marable, Manning; Leith Mullings (2000). Let Nobody Turn Us Around: Voices of Resistance, Reform, and Renewal: an African American Anthology. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 391–392. ISBN 084768346X.

- ^ Vivian, Octavia (2006). Coretta: The Story of Coretta Scott King. Fortress Press. pp. 45. ISBN 0800638557.

- ^ "New Sitdowns Stir Violence in Tennessee". The Chicago Daily Tribune. April 12, 1960.

- ^ King, Jr., Martin Luther (1988). The Measure of a Man. Fortress Press. pp. 9. ISBN 0800608771.

- ^ Theoharis, Athan G.; Tony G. Poveda; Richard Gid Powers; Susan Rosenfeld (1999). The FBI: A Comprehensive Reference Guide. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 148. ISBN 089774991X.

- ^ a b Theoharis, Athan G.; Tony G. Poveda; Richard Gid Powers; Susan Rosenfeld (1999). The FBI: A Comprehensive Reference Guide. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 123. ISBN 089774991X.

- ^ Wilson, Joseph; Manning Marable; Immanuel Ness (2006). Race and Labor Matters in the New U.S. Economy. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 47. ISBN 0742546918. See also: Schofield, Norman (2006). Architects of Political Change: Constitutional Quandaries and Social Choice Theory. Cambridge University Press. pp. 189. ISBN 0521832020.

- ^ Jackson, Thomas F. (2007). From Civil Rights to Human Rights: Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Struggle for Economic Justice. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 85. ISBN 0812239695.

- ^ Shafritz, Jay M. (1998). International Encyclopedia of Public Policy and Administration. Westview Press. pp. 1242. ISBN 0813399742. See also: Loevy, Robert D.; Hubert H. Humphrey; John G. Stewart (1997). The Civil Rights Act of 1964: The Passage of the Law that Ended Racial Segregation. SUNY Press. pp. 337. ISBN 0791433617.

- ^ Glisson, Susan M. (2006). The Human Tradition in the Civil Rights Movement. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 190. ISBN 0742544095.

- ^ a b c King 1998

- ^ Glisson, Susan M. (2006). The Human Tradition in the Civil Rights Movement. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 190–193. ISBN 0742544095.

- ^ "Albany GA, Movement". Civil Rights Movement Veterans. http://www.crmvet.org/tim/timhis61.htm#1961albany. Retrieved on 2008-09-08.

- ^ Garrow, (1986) p. 246.

- ^ Harrell, David Edwin; Edwin S. Gaustad; Randall M. Miller, John B. Boles; Randall Bennett Woods; Sally Foreman Griffith. Unto a Good Land: A History of the American People, Volume 2. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 1055. ISBN 0802829457.

- ^ Jones, Maxine D.; Kevin M. McCarthy (1993). African Americans in Florida: An Illustrated History. Pineapple Press Inc.. pp. 113–115. ISBN 156164031X.

- ^ Haley, Alex (January 1965). "Martin Luther King". The Playboy Interview (Playboy). http://www.playboy.com/arts-entertainment/features/mlk/index.html. Retrieved on 2008-08-27.

- ^ "The Selma Injunction". Civil Rights Movement Veterans. http://www.crmvet.org/tim/timhis64.htm#1964selmainj. Retrieved on 2008-09-08.

- ^ Gates, Henry Louis; Anthony Appiah (1999). Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience. Basic Civitas Books. pp. 1251. ISBN 0465000711.

- ^ Cashman, Sean Dennis (1991). African-Americans and the Quest for Civil Rights, 1900-1990. NYU Press. pp. 162. ISBN 0814714412.

- ^ Schlesinger, Jr., Arthur Meier (2002). Robert Kennedy and His Times. Houghton Mifflin Books. pp. 351. ISBN 0618219285. See also: Marable, Manning (1991). Race, Reform, and Rebellion: The Second Reconstruction in Black America, 1945-1990. Univ. Press of Mississippi. pp. 74. ISBN 0878054936.

- ^ Rosenberg, Jonathan; Zachary Karabell (2003). Kennedy, Johnson, and the Quest for Justice: The Civil Rights Tapes. W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 130. ISBN 0393051226.

- ^ a b Boggs, Grace Lee (1998). Living for Change: An Autobiography. U of Minnesota Press. pp. 127. ISBN 0816629552.

- ^ Aron, Paul (2005). Mysteries in History: From Prehistory to the Present. ABC-CLIO. pp. 399. ISBN 1851098992.

- ^ Singleton, Carl; Rowena Wildin (1999). The Sixties in America. Salem Press. pp. 454. ISBN 0893569828. See also: Bennett, Scott H. (2003). Radical Pacifism: The War Resisters League and Gandhian Nonviolence in America, 1915-1963. Syracuse University Press. pp. 225. ISBN 0815630034. See also: Davis, Rep. Danny (2007-01-16). "Celebrating the Birthday and Public Holiday for Martin Luther King, Jr.". Library of Congress. http://thomas.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/D?r110:46:./temp/~r110JkVd5O::. Retrieved on 2008-08-27.

- ^ Powers, Roger S.; William B. Vogele; Christopher Kruegler; Ronald M. McCarthy (1997). Protest, power, and change: an encyclopedia of nonviolent action from ACT-UP to Women's Suffrage. Taylor & Francis. pp. 313. ISBN 0815309139.

- ^ Moore, Lucinda (2003-08-01). "Dream Assignment". Smithsonian Magazine. http://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/dream-speech.html. Retrieved on 2008-08-27.

- ^ Washington, James M. (1991). A Testament of Hope: The Essential Writings and Speeches of Martin Luther King, Jr.. HarperCollins. pp. 365–367. ISBN 0060646918.

- ^ Washington, James M. (1991). A Testament of Hope: The Essential Writings and Speeches of Martin Luther King, Jr.. HarperCollins. pp. 367–368. ISBN 0060646918.

- ^ Jackson, Thomas F. (2007). From Civil Rights to Human Rights: Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Struggle for Economic Justice. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 222–223. ISBN 0812239695.

- ^ Jackson, Thomas F. (2007). From Civil Rights to Human Rights: Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Struggle for Economic Justice. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 223. ISBN 0812239695.

- ^ Isserman, Maurice; Michael Kazin (2000). America Divided: The Civil War of the 1960s. Oxford University Press US. pp. 175. ISBN 0195091906. See also: Azbell, Joe (1968). The Riotmakers. Oak Tree Books. pp. 176.

- ^ Leeman, Richard W. (1996). African-American Orators: A Bio-critical Sourcebook. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 220. ISBN 0313290148.

- ^ "North Lawndale". Encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org. http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/901.html. Retrieved on 2008-09-08.

- ^ Cohen, Adam Seth; Elizabeth Taylor (2000). Pharaoh: Mayor Richard J. Daley : His Battle for Chicago and the Nation. Back Bay. pp. 360–362. ISBN 0316834890.

- ^ Ralph, James (1993). Northern Protest: Martin Luther King, Jr., Chicago, and the Civil Rights Movement. Harvard University Press. pp. 1. ISBN 0674626877.

- ^ Cohen, Adam Seth; Elizabeth Taylor (2000). Pharaoh: Mayor Richard J. Daley : His Battle for Chicago and the Nation. Back Bay. pp. 347. ISBN 0316834890.

- ^ Cohen, Adam Seth; Elizabeth Taylor (2000). Pharaoh: Mayor Richard J. Daley : His Battle for Chicago and the Nation. Back Bay. pp. 416. ISBN 0316834890. See also: Ralph, James (1993). Northern Protest: Martin Luther King, Jr., Chicago, and the Civil Rights Movement. Harvard University Press. pp. 1. ISBN 0674626877. See also: Fairclough, Adam (1987). To Redeem the Soul of America: The Southern Christian Leadership Conference & Martin Luther King, Jr.. University of Georgia Press. pp. 299. ISBN 0820323462.

- ^ Baty, Chris. Chicago: City Guide. Lonely Planet. pp. 52. ISBN 1741040329. See also: Stone, Eddie (1988). Jesse Jackson. Holloway House Publishing. pp. 59–60. ISBN 087067840X.

- ^ Lentz, Richard (1990). Symbols, the News Magazines, and Martin Luther King. LSU Press. pp. 230. ISBN 0807125245.

- ^ Isserman, Maurice; Michael Kazin (2000). America Divided: The Civil War of the 1960s. Oxford University Press US. pp. 200. ISBN 0195091906. See also: Miller, Keith D. (1998). Voice of Deliverance: The Language of Martin Luther King, Jr., and Its Sources. University of Georgia Press. pp. 139. ISBN 0820320137.

- ^ Mis (2008). Meet Martin Luther King, Jr.. Rosen Publishing Group. pp. 20. ISBN 1404242090.

- ^ Slessarev, Helene (1997). The Betrayal of the Urban Poor. Temple University Press. pp. 140. ISBN 1566395437.

- ^ a b Krenn, Michael L. (1998). The African American Voice in U.S. Foreign Policy Since World War II. Taylor & Francis. pp. 29. ISBN 0815334184.

- ^ Robbins, Mary Susannah (2007). Against the Vietnam War: Writings by Activists. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 107. ISBN 0742559149.

- ^ Robbins, Mary Susannah (2007). Against the Vietnam War: Writings by Activists. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 102. ISBN 0742559149.

- ^ a b Robbins, Mary Susannah (2007). Against the Vietnam War: Writings by Activists. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 109. ISBN 0742559149.

- ^ Lawson, Steven F.; Charles M. Payne; James T. Patterson (2006). Debating the Civil Rights Movement, 1945-1968. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 148. ISBN 0742551091.

- ^ Robbins, Mary Susannah (2007). Against the Vietnam War: Writings by Activists. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 106. ISBN 0742559149.

- ^ Long, Michael G. (2002). Against Us, But for Us: Martin Luther King, Jr. and the State. Mercer University Press. pp. 199. ISBN 0865547688.

- ^ Baldwin, Lewis V. (1992). To Make the Wounded Whole: The Cultural Legacy of Martin Luther King, Jr.. Fortress Press. pp. 273. ISBN 0800625439.

- ^ Harding; Cindy Rosenthal (2006). Restaging the Sixties: Radical Theaters and Their Legacies. University of Michigan Press. pp. 297. ISBN 0472069543. See also: Lentz, Richard (1990). Symbols, the News Magazines, and Martin Luther King. LSU Press. pp. 64. ISBN 0807125245.

- ^ Ling, Peter J. (2002). Martin Luther King, Jr.. Routledge. pp. 277. ISBN 0415216648.

- ^ Franklin, Robert Michael (1990). Liberating Visions: Human Fulfillment and Social Justice in African-American Thought. Fortress Press. pp. 125. ISBN 0800623924.

- ^ King, Jr., Martin Luther; Coretta Scott King; Dexter Scott King (1998). The Martin Luther King, Jr. Companion: Quotations from the Speeches, Essays, and Books of Martin Luther King, Jr.. St. Martin's Press. pp. 39. ISBN 0312199902.

- ^ a b Zinn, Howard (2002). The Power of Nonviolence: Writings by Advocates of Peace. Beacon Press. pp. 122. ISBN 0807014079.

- ^ Zinn, Howard (2002). The Power of Nonviolence: Writings by Advocates of Peace. Beacon Press. pp. 122–123. ISBN 0807014079.

- ^ Vigil, Ernesto B. (1999). The Crusade for Justice: Chicano Militancy and the Government's War on Dissent. University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 54. ISBN 0299162249.

- ^ a b Kick, Russell (2001). You are Being Lied to: The Disinformation Guide to Media Distortion, Historical Whitewashes and Cultural Myths. The Disinformation Campaign. pp. 1991. ISBN 0966410076.

- ^ Isserman, Maurice (2001). The Other American: The Life of Michael Harrington. PublicAffairs. pp. 281. ISBN 1586480367.

- ^ Bobbitt, David (2007). The Rhetoric of Redemption: Kenneth Burke's Redemption Drama and Martin Luther King, Jr.'s "I Have a Dream" Speech. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 105. ISBN 0742529282.

- ^ Ling, Peter J. (2002). Martin Luther King, Jr.. Routledge. pp. 250–251. ISBN 0415216648.

- ^ Yeshitela, Omali. "Abbreviated Report from the International Tribunal on Reparations for Black People in the U.S.". African People's Socialist Party. http://www.apspuhuru.org/publications/repnow/ReparationsNow-OCR.txt. Retrieved on 2008-06-15.

- ^ Lawson, Steven F.; Charles M. Payne; James T. Patterson (2006). Debating the Civil Rights Movement, 1945-1968. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 148–149. ISBN 0742551091.

- ^ "1,300 Members Participate in Memphis Garbage Strike". AFSCME. February 1968. http://www.afscme.org/about/1529.cfm. Retrieved on 2008-08-27.

- ^ "Memphis Strikers Stand Firm". AFSCME. March 1968. http://www.afscme.org/about/1532.cfm. Retrieved on 2008-08-27. See also: Davis, Townsend (1998). Weary Feet, Rested Souls: A Guided History of the Civil Rights Movement. W.W. Norton & Company. pp. 364. ISBN 0393318192.

- ^ Thomas, Evan (2007-11-19). "The Worst Week of 1968, Page 2". Newsweek. http://www.newsweek.com/id/69542/page/2. Retrieved on 2008-08-27.

- ^ Montefiore, Simon Sebag (2006). Speeches that Changed the World: The Stories and Transcripts of the Moments that Made History. Quercus. pp. 155. ISBN 1905204167.

- ^ "United States Department of Justice Investigation of Recent Allegations Regarding the Assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr – VII. King V. Jowers Conspiracy Allegations". United States Department of Justice. June 2000. http://www.usdoj.gov/crt/crim/mlk/part6.htm. Retrieved on 2008-08-27.

- ^ Garner, Joe; Walter Cronkite; Bill Kurtis (2002). We Interrupt this Broadcast: The Events that Stopped Our Lives...from the Hindenburg Explosion to the Attacks of September 11. Sourcebooks, Inc.. pp. 62. ISBN 1570719748. See also: Pepper, William (2003). An Act of State: The Execution of Martin Luther King. Verso. pp. 159. ISBN 1859846955.

- ^ Pilkington, Ed (2008-04-03). "40 years after King's death, Jackson hails first steps into promised land". The Guardian. http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2008/apr/03/usa.race.

- ^ Kirk, John A. (2005). Martin Luther King Jr. Longman. pp. 181. ISBN 0582414318.

- ^ Purnick, Joyce (1988-04-18). "Koch Says Jackson Lied About Actions After Dr. King Was Slain". The New York Times. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=940DEED7133EF93BA25757C0A96E948260. Retrieved on 2008-06-11.

- ^ Lokos, Lionel (1968). House Divided: The Life and Legacy of Martin Luther King. Arlington House. pp. 48.

- ^ "Citizen King Transcript". PBS. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/mlk/filmmore/pt.html. Retrieved on 2008-06-12.

- ^ "1968: Martin Luther King shot dead". On this Day (BBC). 2006. http://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday/hi/dates/stories/april/4/newsid_2453000/2453987.stm. Retrieved on 2008-08-27.

- ^ Klein, Joe. Politics Lost: How American Democracy was Trivialized by People Who Think You're Stupid. New York, Doubleday, 2006. ISBN 978-0385-51027-1, p. 6.

- ^ Manheimer, Ann S. (2004). Martin Luther King Jr: Dreaming of Equality. Twenty-First Century Books. pp. 97. ISBN 1575056275.

- ^ Dickerson, James (1998). Dixie's Dirty Secret: The True Story of how the Government, the Media, and the Mob Conspired to Combat Immigration and the Vietnam Antiwar Movement. M.E. Sharpe. pp. 169. ISBN 0765603403.

- ^ Hatch, Jane M.; George William Douglas (1978). The American Book of Days. Wilson. pp. 321.

- ^ King, Jr., Martin Luther (2007). Dream: The Words and Inspiration of Martin Luther King, Jr.. Blue Mountain Arts, Inc.. pp. 26. ISBN 1598422405.

- ^ Werner, Craig (2006). A Change is Gonna Come: Music, Race & the Soul of America. University of Michigan Press. pp. 9. ISBN 0472031473.

- ^ "AFSCME Wins in Memphis". AFSCME The Public Employee April 1968. http://www.afscme.org/about/1533.cfm. Retrieved on 2008-08-27.

- ^ "1968 Memphis Sanitation Workers' Strike Chronology". AFSCME. http://www.afscme.org/about/1548.cfm. Retrieved on 2008-08-27.

- ^ Ling, Peter J. (2002). Martin Luther King, Jr.. Routledge. pp. 296. ISBN 0415216648.

- ^ a b Flowers, R. Barri; H. Loraine Flowers (2004). Murders in the United States: Crimes, Killers And Victims Of The Twentieth Century. McFarland. pp. 38. ISBN 0786420758.

- ^ a b c d "James Earl Ray Dead At 70". CBS. 1998-04-23. http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/1998/04/23/national/main7900.shtml. Retrieved on 2008-06-12.

- ^ Clarke, James W.. Defining Danger: American Assassins And the New Domestic Terrorists. Transaction Publishers. pp. 297. ISBN 0765802899.

- ^ House Select Committee on Assassinations (2001). Compilation of the Statements of James Earl Ray: Staff Report. The Minerva Group, Inc.. pp. 17. ISBN 0898752973.

- ^ a b Davis, Lee (1995). Assassination: 20 Assassinations that Changed the World. JG Press. pp. 105. ISBN 1572152354.

- ^ "History of the Knoxville Office". FBI. http://knoxville.fbi.gov/hist.htm. Retrieved on 2008-08-27.

- ^ "From small-time criminal to notorious assassin". CNN. http://edition.cnn.com/US/9804/03/james.ray.profile/index.html. Retrieved on 2006-09-17.

- ^ Knight, Peter. Conspiracy Theories in American History: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 402. ISBN 1576078124.

- ^ "Questions left hanging by James Earl Ray's death". BBC. 1998-04-23. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/americas/82893.stm. Retrieved on 2008-08-27.

- ^ Frank, Gerold (1972). An American Death: The True Story of the Assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Greatest Manhunt of our Time. Doubleday. pp. 283.

- ^ "James Earl Ray, convicted King assassin, dies". CNN. 1998-04-23. http://edition.cnn.com/US/9804/23/ray.obit/#2. Retrieved on 2006-09-17.

- ^ "Trial Transcript Volume XIV". The King Center. http://www.thekingcenter.org/tkc/trial/Volume14.html. Retrieved on 2008-08-27.

- ^ Smith, Robert Charles; Richard Seltzer (2000). Contemporary Controversies and the American Racial Divide. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 97. ISBN 074250025X.

- ^ Pepper, William (2003). An Act of State: The Execution of Martin Luther King. Verso. pp. 182. ISBN 1859846955.

- ^ Sargent, Frederic O. (2004). The Civil Rights Revolution: Events and Leaders, 1955-1968. McFarland. pp. 129. ISBN 0786419148.

- ^ "United States Department of Justice Investigation of Recent Allegations Regarding the Assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.". USDOJ. http://www.usdoj.gov/crt/crim/mlk/part2.htm#over. Retrieved on 2008-08-27.

- ^ Canedy, Dana (2002-04-06). "My father killed King, says pastor, 34 years on". The Sydney Morning Herald. http://www.smh.com.au/articles/2002/04/06/1017206269495.html. Retrieved on 2008-08-27.

- ^ Branch, Taylor (2006). At Canaan's Edge: America in the King Years, 1965-68. Simon & Schuster. pp. 770. ISBN 9780684857121.

- ^ Goodman, Amy; Juan Gonzalez (2004-01-15). "Jesse Jackson On "Mad Dean Disease," the 2000 Elections and Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King". Democracy Now!. http://www.democracynow.org/2004/1/15/rev_jesse_jackson_on_mad_dean. Retrieved on 2006-09-18.

- ^ Downing, Frederick L. (1986). To See the Promised Land: The Faith Pilgrimage of Martin Luther King, Jr. Mercer University Press. pp. 246–247. ISBN 0865542074.

- ^ Kotz, Nick (2005). Judgment Days: Lyndon Baines Johnson, Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Laws that Changed America. Houghton Mifflin Books. pp. 233. ISBN 0618088253.

- ^ "King Encyclopedia". Stanford University. http://stanford.edu/group/King/about_king/encyclopedia/levison_stanley.htm. Retrieved on 2008-08-27.

- ^ Woods, Jeff (2004). Black Struggle, Red Scare: Segregation and Anti-communism in the South, 1948-1968. LSU Press. pp. 126. ISBN 0807129267. See also: Wannall, Ray (2000). The Real J. Edgar Hoover: For the Record. Turner Publishing Company. pp. 87. ISBN 1563115530.

- ^ a b Ryskind, Allan H. (2006-02-27). "JFK and RFK Were Right to Wiretap MLK". Human Events. http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qa3827/is_200602/ai_n17173432/pg_2. Retrieved on 2008-08-27.

- ^ a b c d Christensen, Jen (2008-04-07). "FBI tracked King's every move". CNN. http://www.cnn.com/2008/US/03/31/mlk.fbi.conspiracy/index.html. Retrieved on 2008-06-14.

- ^ Garrow, David J. (2002-07/08). "The FBI and Martin Luther King". The Atlantic Monthly. http://www.theatlantic.com/doc/200207/garrow.

- ^ Washington, James M. (1991). A Testament of Hope: The Essential Writings and Speeches of Martin Luther King, Jr.. HarperCollins. pp. 362. ISBN 0060646918.

- ^ Bruns, Roger (2006). Martin Luther King, Jr.: A Biography. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 67. ISBN 0313336865.

- ^ Gilbert, Alan (1990). Democratic Individuality: A Theory of Moral Progress. Cambridge University Press. pp. 435. ISBN 0521387094.

- ^ Kotz, Nick (2005). Judgment Days: Lyndon Baines Johnson, Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Laws that Changed America. Houghton Mifflin Books. pp. 70–74. ISBN 0618088253.

- ^ Washington, James M. (1991). A Testament of Hope: The Essential Writings and Speeches of Martin Luther King, Jr.. HarperCollins. pp. 363. ISBN 0060646918.

- ^ Sidey, Hugh (1975-02-10). "L.B.J., Hoover and Domestic Spying". Time. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,912799-2,00.html. Retrieved on 2008-06-14.

- ^ a b "FBI tracked King's every move". CNN. http://www.cnn.com/2008/US/03/31/mlk.fbi.conspiracy/index.html#cnnSTCVideo. Retrieved on 2008-08-27.

- ^ Newsweek Magazine 1-19-1998, page 62; "And the walls came tumbling down," by Rev. Ralph Abernathy (1989)

- ^ Baldwin, Lewis V. (1992). To Make the Wounded Whole: The Cultural Legacy of Martin Luther King, Jr. Fortress Press. p. 296. ISBN 0800625439.

- ^ "And the Walls Came Tumbling Down by Rev. Ralph David Abernathy". Booknotes. 1989-10-29. http://www.booknotes.org/Transcript/index_print.asp?ProgramID=1442. Retrieved on 2008-06-14.

- ^ Bearing the Cross: Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. William Morrow & Company. 1986. See also: Burrow, Jr., Rufus (Spring 2003). "The humanity of Martin Luther King, Jr.: Vigilance in pursuing his dream". Encounter. http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qa4044/is_200304/ai_n9232227. Retrieved on 2008-06-14.

- ^ Burnett, Thom (2005). Conspiracy Encyclopedia. Collins & Brown. pp. 58. ISBN 1843402874.

- ^ Thragens, William C. (1988). Popular Images of American Presidents. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 532. ISBN 031322899X.

- ^ "FBI letter to King". Oil Empire. http://www.oilempire.us/cointelpro.html. Retrieved on 2008-08-27. See also: Kotz, Nick (2005). Judgment Days: Lyndon Baines Johnson, Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Laws that Changed America. Houghton Mifflin Books. pp. 247. ISBN 0618088253.

- ^ Wilson, Sondra K. (1999). In Search of Democracy: The NAACP Writings of James Weldon Johnson, Walter White, and Roy Wilkins (1920-1977). Oxford University Press US. pp. 466. ISBN 019511633X.

- ^ Church, Frank (April 23, 1976). "Church Committee Book III". Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Case Study. Church Committee. http://www.icdc.com/~paulwolf/cointelpro/churchfinalreportIIIb.htm. Retrieved on 2008-08-27.

- ^ Phillips, Geraldine N. (Summer 1997). "Documenting the Struggle for Racial Equality in the Decade of the Sixties". Prologue Magazine. The National Archives and Records Administration. http://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/1997/summer/equality-in-the-sixties.html#f3. Retrieved on 2008-06-15.

- ^ "Eyewitness to Murder: The King Assassination Featured Individuals". Black in America. CNN. http://www.hvc-inc.com/clients/cnn/bia/featured.html. Retrieved on 2008-06-16.

- ^ McKnight, Gerald (1998). The Last Crusade: Martin Luther King, Jr., the FBI, and the Poor People's Crusade. pp. 76. ISBN 0813333849.

- ^ Martin Luther King, Jr.: The FBI Files. Filiquarian Publishing, LLC. 2007. pp. 40–42. ISBN 1599862530. See also: Polk, James (2008-04-07). "King conspiracy theories still thrive 40 years later". CNN. http://www.cnn.com/2008/US/03/28/conspiracy.theories/index.html. Retrieved on 2008-06-16. and "King's FBI file". FBI. http://foia.fbi.gov/foiaindex/king.htm. Retrieved on 2008-08-27.

- ^ Knight, Peter. Conspiracy Theories in American History: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 408–409. ISBN 1576078124.

- ^ Ansell, Gwen (2005). Soweto Blues: Jazz, Popular Music, and Politics in South Africa. Continuum International Publishing Group. pp. 139. ISBN 0826417531. See also: Clinton, Hillary Rodham (2007). It Takes a Village: And Other Lessons Children Teach Us. Simon & Schuster. pp. 137. ISBN 1416540644.